|

| 900 3rd St SE: Loftus Lofts (186 units) under construction |

|

| 1014 2nd St SE, 2012: Where the Row Houses are now (Google Earth screenshot) |

|

| Big plans for New Bohemia: 2019 Action Plan, p. 40 |

It's still a work in progress, and ten years from now it will still be a work in progress, so we are far from pronouncing a final verdict, even as some of that open space gets filled up. Quite a few residential units, mostly apartments and condominiums, have responded to the gap in housing, with more in process or proposed.

| ||

| Adaptive reuse: Water Tower Place Condominiums, 900 2nd St SE |

|

| Compatible construction: Row Houses on Second, 1008-1018 2nd St SE |

900 3rd St SE: Loftus Lumber site under construction by Conlon Construction, to be five-story mixed-used property including 186 market-rate apartments ranging from studio to (two) two-story lofts. [In the Action Plan, the 10th Avenue side is projected to be a "shared space street."]

|

| Loftus Building, taken from the Cherry Building |

1000 block of 2nd St SE: Conlon Construction proposed a 150-room hotel plus 10 townhomes between 2nd Street and the river, across the street from the Row Houses, on what is now part of a long parking lot. [In the Action Plan, this land is projected for apartments.]

|

| Future hotel site? The federal courthouse is in the background |

116 16th Av SE: Darryl High wants to build Vesnice, consisting of one six-story residential building (63 units) facing the river and one four-story mixed use building facing 2nd St with 22 residential units above 1443 sq ft of commercial space. [In the Action Plan, this land is projected for apartments.]

1600 and 1700 blocks of 2nd St SE: Chad Pelley has bought land (from Brett "Bo Mac" McCormick), and intends to purchase additional city-owned parcels on both sides of 2nd Street.

|

| View from the riverside trail of the property under construction, New Bo Lofts in the distance |

|

| Looking towards the river from the cul-de-sac at the end of 2nd St, National Czech and Slovak Museum in the distance |

Besides these, the Matyk Building, which until recently housed the delightful but financially unsustainable Bohemian (1029 3rd Street SE), is up for sale. Asking price is over $700,000, about double the assessed value. Maybe the hope is someone sees the future value of that land surging? And uses it to build... what? (The only reason I can think of that someone would pay double the assessed value for a property is because they believe it would bring more value with a more intensive use.)

|

| For sale: Matyk Building |

While 1st Avenue East empties out, building and occupying are going gangbusters in New Bohemia. Demand is clearly here, not there. Marissa Payne in the Gazette attributes that to "[t]he NewBo District's arts and cultural scene, entertainment options and a mix of restaurants." Community Development Director Jennifer Pratt told the Gazette: "It is a continuation of what we've seen since the reinvestment after the 2008 flood.... We definitely saw in the market that people were interested in walkable neighborhoods. That has just continued to grow" (Payne 2024).

☁

Friends of New Bohemia are beginning to express anxiety about all the development. A lot of the newest construction has been of the cookie-cutter variety, and some of the proposals are relatively huge. Given that a lot of New Bo's allure relates to its historical character, it should be a no-brainer to insist on compatible form. In the words of the city's Assistant Community Development Director Adam Lindenlaub, "There's an aspect of character that is unique here that you don't see in other parts of the city" (Payne 2024). Beyond that, though, you don't own your view, and when all is working well, the core neighborhoods will be the densest and most valuable in the city.

Inevitably, a lot of the concerns about development in New Bohemia center on parking, particularly for major events. If parking is used by residents, where are the rest of supposed to park? they ask. Sigh. It should no longer be debatable that parking is the enemy of vibe, not to mention wasteful of city finances and land) and no place with plenty of parking is worth visiting (see, for example, Grabar 2023). In this car-dependent city, though, we always imagine ourselves one surface parking lot away from paradise.

.png) |

| Is this heaven? No, but it has a lot of parking! (New Bohemia on Google Earth, 2019) |

And yet, the parking-concerned are not wrong to sense an issue, because New Bohemia has developed in a way that is heavily dependent on traffic from outside, which in the vast majority of cases is going to arrive by personal car. (So has Downtown. Don't even start me on the casino, which the Gazette reports is now Miss America-approved.)

This, then is the real issue: New Bohemia, though still a work in progress, has become a suburb. It is "walkable," to recall Pratt's description, but only for entertainment, and even then walkers must contend with many moving vehicles in search of the same entertainment. Other than that it is a bedroom community. The Czech Village/New Bohemia Main Street District claimed 250 businesses in 2022, but few are significant employers. Schools, groceries, hardware, and pharmacies are far away, and bus service is spotty. There isn't a park (though the west side Greenway will be close by once it's built).

|

| Stoney Point, August 2013: More houses, fewer apartments and bars |

The only difference between New Bohemia and, say, the world of Leave It to Beaver, is most of New Bo's housing is multifamily and there are a lot of bars. Maybe too many? The closures of Chrome Horse and Bo Mac's are possibly signs that such an economic monoculture is not sustainable, particularly when bigger newer bars (like Big Grove in Kingston) inevitably come along.

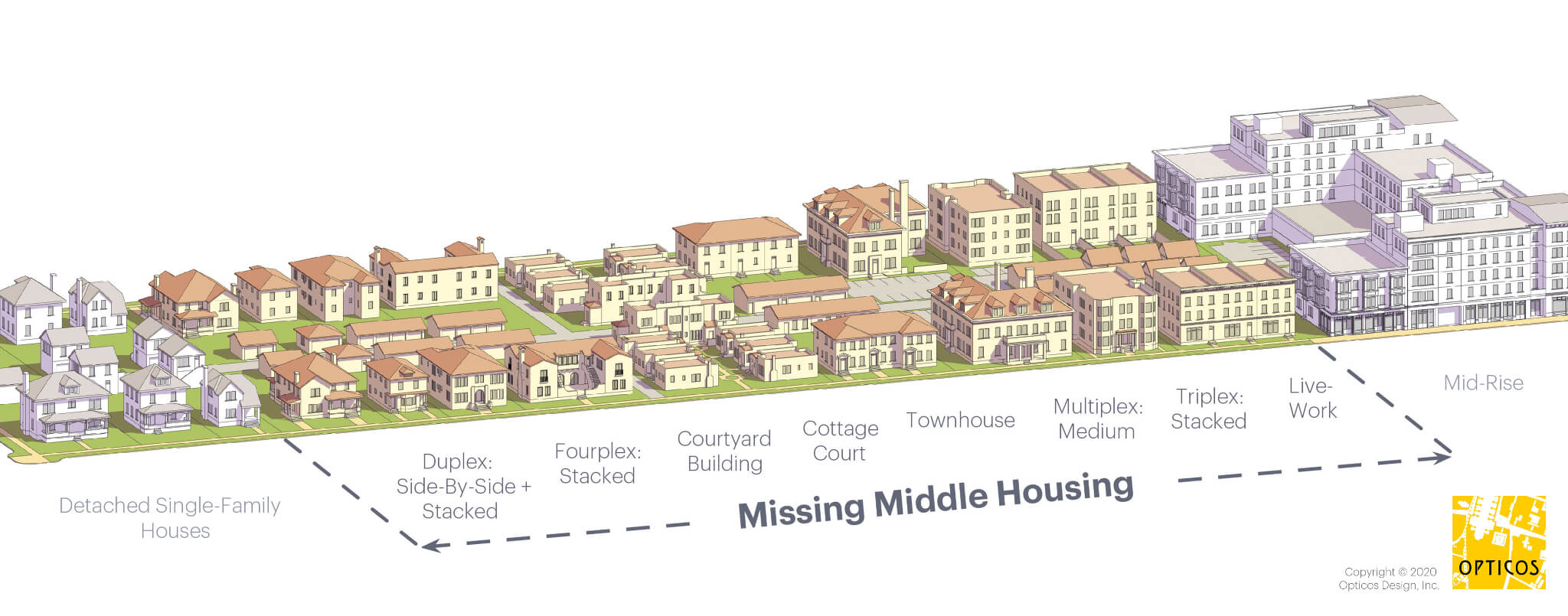

With apologies to Andres Duany, the transect in Cedar Rapids starts with commercial playgrounds in the center, surrounded by a moat of emptiness (MedQuarter, I-380, parking lots for the impending casino); beyond these are residential areas, where getting almost anywhere requires a car. Beyond those are greenfields, waiting to be subdivisions, or part of a wider I-380. Maybe all this was inevitable, but it is indeed regrettable. At least the city should stop subsidizing more of this sort of development.

SOURCE: Marissa Payne, "New Development Coming to NewBo," Cedar Rapids Gazette, 7 September 2024, 1A, 10A

SEE ALSO: "More New, Less Bo?" 4 July 2022

"Where are the Metro's Destinations Heading?" 28 July 2021

"Bridging the Bridge," 26 June 2019

"Envisioning CR I: A 24-Hour Downtown," 1 March 2015

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this post named the former owner of the Matyk Building. It has been updated, with passive voice being used.