|

| Green Line departing East Bank stop |

Jarrett Walker, Human Transit: How Clearer Thinking about Public Transit Can Enrich Our Communities and Our Lives (Island, revised ed, 2024)

Jarrett Walker is out with a new edition of Human Transit, first published in 2011. Walker is a transportation planner, consultant and blogger from whom I've learned a lot about what works and doesn't when it comes to public transportation. I particularly appreciated his insight, explored in the first edition, that any transit system faces a tradeoff between frequency, coverage area, and the ol' budget. Since I've already used those insights to analyze Cedar Rapids transit, and since I had cause to be in Minneapolis this week, it's a chance to examine Walker's ideas in light of the Twin Cities' Metro Transit, a system with which I'm relatively unfamiliar. As it happens, Walker consulted in the Twin Cities, albeit quite a few years ago (Walker 2009).

The fundamental problem addressed in Human Transit is how to move large numbers of people within a small space. Walker refers in the introduction to three efficiencies of transit over cars--space, labor (one driver for many passengers), and strain on the environment (2023: 15)--and pollution, climate, and public health concerns get a few mentions elsewhere in the book, but essentially we're asking how to make the transit we can afford work for the people we've got. It takes as written the aggregation advantages of cities, and that people are living in dense metros for those very advantages.

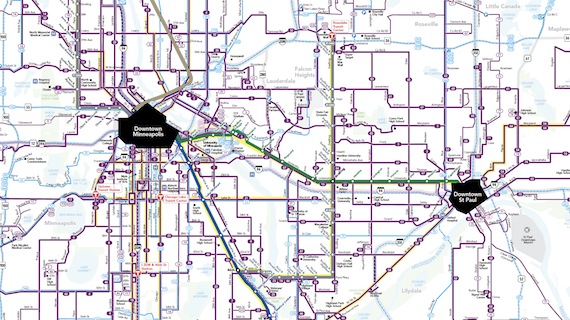

|

| Metro Transit system map |

Even in densely-populated cities, most people must have positive reasons to take transit. Walker focuses on seven common "demands" (expectations) in ch 2:

(1) Connectivity. Are the stops convenient enough to my home and destinations that I can leave the car in the garage or not have a car at all? If I can't get where I'm going on a single line--unlikely in an efficient system consisting of multiple straight lines--are connections easy to manage?

This is especially hard for a tourist to judge. We stayed at the Graduate Hotel, three blocks from the University of Minnesota's main campus, and kitty-corner from the East Bank station on the light-rail Green Line. We took the Green Line east to the A-Line BRT, then rode that line south to Grand Avenue, at the entrance of Macalester College. The transfer to the A-Line was a bit tricky, as it involved walking swiftly across both University and Snelling, both wide and heavily trafficked streets, to get to the bus stop.

|

| View from the bus stop on an A-Line; despite the important transit junction, the area is noticeably rundown |

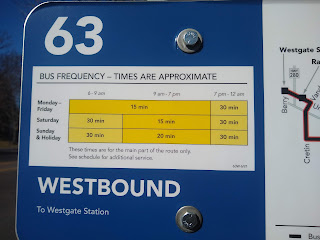

On the way back, we took the #63 bus to meet the Green Line at Raymond Avenue. It was not noticeably longer than the journey there, particularly because the train came almost as soon as we got off the bus.

(2) Span and frequency (covered in ch 8). Does the system run enough of the day that I can get to work or school and maybe evening events?

The first St. Paul-bound train on the Green Line rolls through East Bank at 5:21 a.m. Trains come every 15 minutes beginning at 6, only slowing down at 10:30 p.m. The last train arrives at 11:36. Saturday and Sunday schedules are pretty similar.

|

| In 2016 I took the Green Line to its terminus at Target Field where I ran into Tony Oliva |

(3) Time. How long does it take to get where I'm going, including and maybe especially the time to get to the station and wait for the bus or train to arrive?

According to Google Maps, it takes 33 minutes in mid-afternoon to get from our hotel to the Macalester College campus by transit, as opposed to 14 by car. If we add in an average wait time of 7.5 minutes for the train, we're at 40.5, plus managing the transit. We got to the East Bank light-rail station just as a train was pulling out, so we waited the full 15. We had about 7 minutes on Snelling Avenue once we'd navigated the intersection, though it seemed longer in the scruffy surroundings, so the total was about 45 minutes.

|

| Waiting for the train at East Bank |

A 45 minute transit run in lieu of a 14 minute drive was still worth it for me, the tourist, because I didn't have to deal with traffic and parking. But if I worked at or near Macalester, I'd probably have my own parking space. (In Washington, D.C., by comparison, the transit time to car time ratio outside of rush hour is maybe 2-1 instead of 3-1.)

(4) Fares (ch 11). How painless is it to pay to ride? For regular riders, there are 7-day and 31-day options which can be loaded onto one's plastic Go-To Card. For tourists, an all-day pass is $5, good for both rush hour and non-rush hour, and usable on all local lines. (A single ride is $2.50 during rush hour, $2 otherwise.)

I bought my all-day pass on the Metro Transit app, so it was on my phone, while Jane bought a paper ticket at the East Bank station.

|

| Fare kiosks |

|

| All day passes are $5 on weekdays, $4 on weekends |

(5) Civility, mainly of station agents and conductors, but I'd include conditions on the bus or train. Because of the seemingly lax enforcement, we had no interactions with transit employees. Conditions on the vehicles we rode Friday (three separate light-rail trains, one A-line bus, one #63 bus) were a mixed bag.

|

| Interior, eastbound light rail train |

None of the vehicles was crowded, as we did start our travels til after 9:00 a.m. There was a strong marijuana smell on two of the trains, and one train had several passengers who were clearly living temporarily in the train cars. Saturday night on my way back to the hotel on the Green Line, I unwittingly boarded into a drug party that was well underway; I debarked as soon as I could, and trotted to the next car which proved to be a better fit.

(6) Reliability. Can I count on the system to get me where I'm going on time? The vehicles were all on time or very close to it, even though we heard announcements that the Green Line was running slowly due to track issues.

(7) Legibility. If I change my plans at the last minute, is it clear what my new route is? I'd use the Maps app on my phone rather than try to use system resources, whatever city I was in. There aren't system maps about in the Twin Cities, or even route maps for the light rail or BRT.

|

| Grand Avenue and Snelling: when the bus comes |

SEE ALSO:

|

| Washington Avenue: Both metro and university buses drive along the light rail track, which is ever-so-gently separated from the street |

No comments:

Post a Comment