|

| Pedestrian mall by Baruch College, New York City (Wikimedia commons) |

Where you sit strongly affects where you stand on issues like traffic and parking. Some cities, like New York, San Francisco or Seattle have the crowds and the confidence to consider closing streets, instituting congestion pricing for auto traffic (see also Trumm 2019 on Seattle), and charging market rates for parking (Shoup 2005).

The brilliant work of Professor Donald Shoup, and articles like this one from Grist with the headline "Cities Finally Realize They Don't Need to Require So Much Damn Parking," are centered in this first category of towns. Grist's examples are Chicago, New York, Seattle and Washington, D.C.--though they also note Buffalo and Fayetteville have eliminated ordinances requiring parking minima for development. Shoup, a professor at UCLA, does a lot of his empirical research in his hometown of Los Angeles.

Legacy industrial cities, on the other hand, are staring into the abyss of obsolescence; they need more traffic, and have plenty of parking. Ditto many small towns and rural areas.

|

| Surface parking lot on a Tuesday afternoon, New Bohemia neighborhood |

|

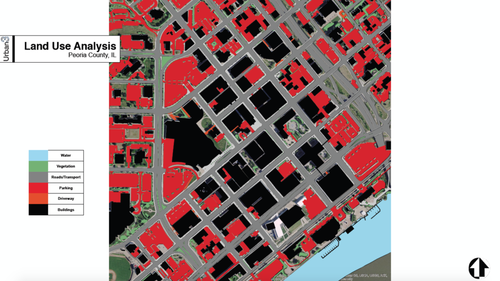

| Parking areas in downtown Peoria, Illinois (Source: Urban 3) |

|

| Strip mall parking lot, Black Friday 2015 |

I would characterize the pro-parking argument this way: The city needs to provide the largest amount of parking space it can, free of charge, because: (1) shoppers, employees and those who attend events have come to appreciate the convenience of door-to-door driving; (2) Cedar Rapids consumer businesses are mostly competing on price and convenience (with the strip malls and big-box stores, with the Internet) rather than on vibe or experience; and (3) there's no particular reason not to.

Shoup's empricial study of the Westwood Village area of Los Angeles found drivers spending an average of 3+ minutes looking for parking. His answer is to charge the market price for parking, which he defines as the price that leaves one meter free on every block. Cedar Rapids residents, goes the argument, have a market price for parking that is near zero, and little appetite to search for spaces, because they have choices. So anything other than plenteous free parking will doom businesses and piss off voters.

|

| Free on-street parking, 3rd St SE |

|

| Lincoln Square, North Lincoln Avenue, Chicago Note that placement on this one-lane, one-way block reduces car-bike conflict |

Even larger parking areas can in some cases support urbanist development, if they're moved away from the action (Kaplan 2015). Using the example of 2nd Street SE downtown, Ben notes, "This stretch of downtown is all parking lots, loading zones, and blank walls. It's also necessary. This space functions as a repository for all the stuff you need to help 1st Street and 3rd Street be great streets." Similar phenomena can be observed on 15th and 17th Avenues SW, flanking the re-emergent heart of Czech Village that is 16th Avenue; the lengthy and capacious Lot 44 (pictured above), on the river side of New Bohemia; and Henry Street in Decorah, which makes Water Street possible. Rochester, Minnesota has incredibly dense development around the Mayo Clinic, facilitated by emptier areas that surround it, though as the Downtown Master Plan (2010: 31) notes, "the fringe areas... often exhibit a pattern of development, including many blocks of surface parking lots, which does not provide either a gentle transition from Downtown or a strong edge." In 2019, we need parking areas, but too much parking can strangle development.

|

| Edge of downtown Rochester |

- it warps urban form, because there are parking lots where there could be housing, stores or restaurants;

- it removes potentially productive land from use;

- it frustrates walkers by placing destinations farther apart;

- it amounts to a subsidy of driving by non-drivers, because the parking spaces are paid for with tax money; and so

- it incentivizes driving of private cars, as opposed to other, more environmentally- and fiscally-friendly forms of transportation.

Strip malls and big-box stores are not financially productive places (Quednau 2017); let's stop building them, and let's stop subsidizing their existence. We could charge market prices for parking, and use the revenue to fund improvements in the area (Shoup 2005, chs 15-21)--including, if the situation warrants, municipal parking garages--compatibly designed, of course.

Nevada City, California, recently raised their meters to $1/hour from 25 cents, with the revenue dedicated to fire protection; even then, it should be said, merchants and residents are ambivalent (Bliss 2019).

More housing and offices closer to "the action" will provide a 24-hour population that doesn't need to drive to get there. Encourage owners of large parking lots needed at different times (churches, clinics, restaurants) to share facilities rather than having their separate lots vacant most of the time (Herriges 2018). Improve public transportation near active places, like between Kingston Village and New Bohemia. Provide non-financial support for local business development (Mitchell 2017). Help, or at least allow the core areas of our town to become places where people want to be, and where businesses need to be.

|

| Town and Country Mall, Black Friday 2015 |

We need to acknowledge that the places we build, and how they evolve in the future, result from choices--not inevitability, not nature, but our choices. If we are not making the choices, someone else is making the choices for us. So, what kinds of places are we choosing? The great Danish architect-designer Jan Gehl says in the documentary "The Human Scale:"

We have known this about the motorcar: If you make more roads, you will have more traffic. Now we know about cities: If you make more places for people, you will have more public life. In cities that have done away with their public spaces, life has become totally privatized (quoted at Borys 2018).So, what kinds of places are we choosing to build? What values are we choosing with? You can't parking lot your way to public life.

|

| Former K-Mart, Black Friday 2017 |

Donald Shoup, The High Cost of Free Parking (Planners Press, rev ed, 2011)

Jeff Speck, Walkable City Rules: 101 Steps to Making Better Places (Island Press, 2018)

PREVIOUS POSTS:

"Hiking the (Parking) Crater," 25 January 2018

"Black Friday Parking 2017: After the Ball is Over," 24 November 2017

"Downtown vs. Parking," 29 September 2013

"The Parking Dilemma," 31 July 2013

One more video: