|

| Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, principal architect of the Senate Republican health care bill |

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) Monday released its assessment of the effects of the bill: the number of insured Americans will decline by 22 million in 10 years, while the federal deficit will decline by a total of $321 billion. The deficit reduction could in theory be greater, but the bill also repeals the tax increases on upper brackets included in the 2010 law (Kaplan and Pear). The CBO did not to my knowledge assess whether the law would fulfill President Trump's April promise that individual premiums and deductibles, which have risen pretty steadily for more than 30 years, would be "much lower," but a collection of health economists and policy experts consulted by The New York Times predict many people will face substantially higher deductibles, or premiums, or both. Rodney L. Whitlock, a former Senate Republican policy assistant, thought deductibles would reach "almost assuredly five digit" territory (Adelson).

Obamacare was passed after more than six decades of effort to pass a national health insurance bill that had previously yielded government health programs for the elderly (Medicare, passed in 1965) and the poor (Medicaid, also passed in 1965) as well as a series of bloodied presidents who attempted broader approaches. The policy window was open only because Democrats briefly had a "filibuster-proof" Senate majority of 60-40, and because provider groups were willing to negotiate with the administration which they had not been in the 1990s when Bill Clinton was President. A few Republicans were involved in policy talks in the summer of 2009, but withdrew coincident with the rise of the grass roots conservative movement known as the Tea Party.

|

| President Harry S Truman (1945-53) advocated an early national health program |

- Lack of insurance. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 15 percent of non-elderly Americans lacked insurance in 2013, a proportion that had been pretty consistent dating back to the 1980s. They weren't always the same 15 percent, as people cycled in and out of employment or eligibility for Medicaid, so the percentage of people with inconsistent access to insurance was somewhat higher. Lack of insurance is associated with major health problems, shorter life expectancies, inconsistent care and financial stress.

- Under-insurance. This is harder to measure, but a large population had health insurance that didn't actually cover what they ultimately needed, due to limits on benefits, exemptions for pre-existing conditions, or what wasn't covered by the policy to begin with. This has contributed to the rise of crowdfunding appeals to pay for unanticipated health care expenses.

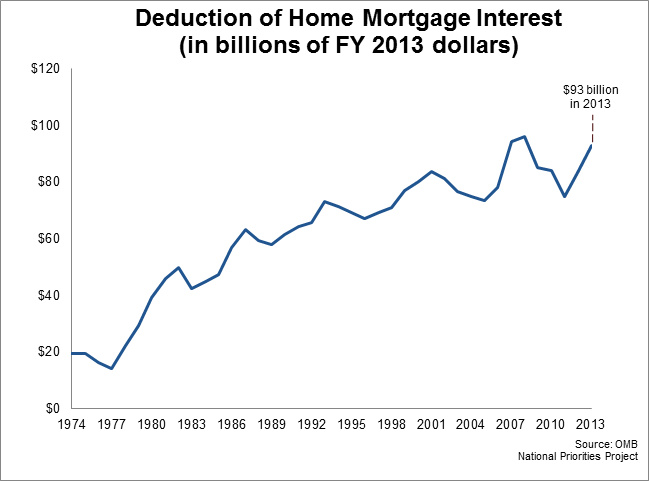

- Rising costs. Health care inflation had been running well ahead of the consumer price index at least since 1980, when health care spending amounted to about 1/12 of U.S. gross domestic product. It is now about 1/6 of GDP, placing financial stress on consumers, businesses that provide health insurance for their employees, and governments at all levels.

The existence of these three problems created substantial obstacles to opportunity in America. In a country that prides itself on meritocracy, the ability to rise is handicapped when accident of birth dooms some of us to inferior health care, not to mention housing, education and so on.

|

| President Barack Obama, for whom the Affordable Care Act of 2010 was a primary legislative achievement |

Serious health care policy makers note Obamacare needs fixing:

- Costs continue to rise, after a hiatus early in the decade which may have been a fluke, or may have been a temporary effect of the severe recession which dampened demand for just about everything. Health care inflation didn't start with Obamacare, but is unsustainable and will doom the program even if nothing else does.

- Insurance exchanges have had an uneven record in practice, even after the initial enrollment bugs were worked out. Many counties have one or zero companies offering policies to individuals, which doesn't provide consumers with any benefits of competition. A more stable basis for the program would surely help.

- Millions of people have been added to insurance rolls, but millions more remain outside. The proportion of uninsured non-elderly Americans dropped from 15 percent in 2013 to 10 percent in 2015, but still, 10 percent. Weak penalties for not buying insurance were probably understandable early on, but the "introductory rate" era is past and they must be strengthened if coverage of the long-term ill is going to be sustainable. (See comments by Dan Mendelson, president of Avelere Health, on Morning Edition Monday.)

|

| President Donald J. Trump has not been involved in the policy making process, and his statements on health care have been vague and contradictory |

Ending mandates on policy coverage, having insurance and community rating would lower the costs of policies for some, while driving it up for others. Moreover, without the individual mandate the viability of the mandate for pre-existing conditions would be doubtful, though the Senate bill has added a "lockout" provision requiring a six-month waiting period for getting insurance if one has let previous coverage lapse. What Brookings analysts concluded about the House bill--In general, enrollees who are younger, have higher incomes, or live in low-cost areas are most likely to be better off, while enrollees who are older, have lower incomes, or live in high-cost areas are most likely to be worse off (Brandt et al.)--is probably true of the Senate bill as well.

If access to health care is to remain part of our common life, it requires more than holding the line on repealing the Affordable Care Act. It requires advocates, because the complex set of system patches created by the ACA could be starved of funding more easily than it could be repealed by law. ("Perhaps let OCare crash and burn!" tweeted the President Monday morning, noting repeal is "Not easy!") Ensuring access while controlling costs is surely difficult, though the parties and interests in this ongoing policy process are making it more difficult than it needs to be, given the experience of other industrial democracies. That means seriously addressing the market failures (information, competition, merit goods) endemic to privately-produced health care. I don't know if that's even possible in such a polarized political environment, but signs of unrest in the states offer some hope.

EARLIER POST: "Health Care," 4 May 2013

DATA FROM KAISER FAMILY FOUNDATION

"Health Insurance Coverage of Nonelderly" (2013-2015)

"Premiums and Tax Credits Under the Affordable Care Act vs. the Senate Better Care Reconciliation Act," 23 June 2017

POLITICAL ANALYSIS: Nate Silver, "Mitch McConnell Isn't Playing 13-Dimensional Chess," FiveThirtyEight, 27 June 2017