Almost a decade removed from the foreclosure crisis that began in 2008, the nation is facing one of the worst affordable-housing shortages in generations. The standard of “affordable” housing is that which costs roughly 30 percent or less of a family’s income. Because of rising housing costs and stagnant wages, slightly more than half of all poor renting families in the country spend more than 50 percent of their income on housing costs, and at least one in four spends more than 70 percent. Yet America’s national housing policy gives affluent homeowners large benefits; middle-class homeowners, smaller benefits; and most renters, who are disproportionately poor, nothing. It is difficult to think of another social policy that more successfully multiplies America’s inequality in such a sweeping fashion.— MATTHEW DESMOND (2017)

What do you buy when you buy a house? According to the title, you’ve purchased a dwelling and the land on which it sits, as well as additional property as specified. And one would be foolish to make the purchase without ensuring that both are in sound condition: the yard drains properly and is can accommodate your pets or children; there’s a secure place for your car(s); the roof is in good shape, the basement doesn’t flood and isn’t filling up with radon, the kitchen’s up to date, and such like.

Most people take additional factors into account, which aren’t

included in the title to the house: the qualities of the neighborhood,

access to parks and schools, and the view from the living room window, for example. Change

happens, and none of those amenities are legal entitlements, but they can be sources of

powerful emotional attachment.

Perhaps more importantly, for most American homeowners, their house is

their major asset, representing by far the largest portion of their material wealth.

According to the Federal Reserve Board,

housing wealth in the United States is about one half of overall household net worth. Mess with the monetary value of housing and you're into people's pockets in a big way.

So it’s entirely understandable that homeowners react

defensively when they hear of new development in their neighborhood, whether it’s

low-income apartments, live-work spaces or even adding a sidewalk while narrowing the street. It's too easy to imagine change will involve noise, traffic, crime and/or drainage issues that are hard to fix once they're established. One of the costs of seven decades of bad development is that all development gets perceived as bad.

But "density doesn't have to be scary, if it's done right," says Bay Area designer Karen Parolek (Holeywell). A fourplex like this...

|

| Fourplex, Portland OR (Source: Wikimedia commons) |

...wouldn't look out of place in my streetcar suburban neighborhood.

The problem with protecting our neighborhoods from changes is that it harms the ability of other people to enjoy the quality of life we want to enjoy, and leaves them worse off.

- Everyone has the right to shelter. I doubt I could convince you if you believe otherwise, but it seems fairly basic.

- Children in areas of concentrated poverty do less well than if they live in more socioeconomically mixed areas (Chetty et al. 2015). Adults in areas of concentrated poverty have less access to economic opportunity and lower length and quality of life (Kneebone et al 2011 esp Box 1, Ludwig 2014).

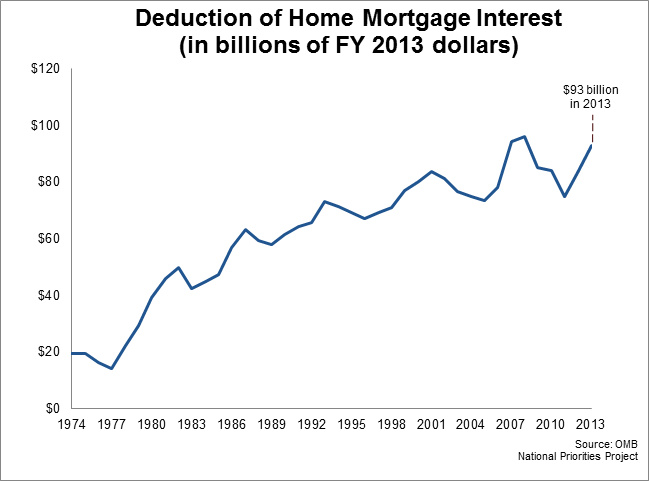

- Governments are nowhere fiscally flush enough to build the infrastructure that would allow people to live in enclaves. This hasn’t stopped them from doing it for the last several decades, of course. Between intracity highways, the home mortgage interest deduction and an unwillingness to address the externalities of driving, governments at all levels have been giving big assists to their better-off constituents. (Because you have to claim more than the standard deduction to make the mortgage interest deduction worth it, more than 80 percent of tax expenditures under it go to households making more than $100,000 per year.) The federal government spends more money on the home mortgage interest deduction ($71B in 2015) than on housing assistance—even before the latter’s 13.2 percent cut in President Trump’s FY18 budget. This has reinforced disparities in wealth dating from the original discriminatory form of housing programs (Desmond 2017).

|

| Source: nationalpriorities.org |

So what should we do about housing policy in America? There are some ideas out there...

- Zoning of neighborhoods should be inclusionary not exclusionary: Economist Joe Cortright (2017) notes “having a wide variety of housing types and sizes can also make room for people of a wide variety of incomes.” Ease the permitting process for multi-unit “missing middle” housing (as is being attempted by CodeNEXT in Austin, Texas)

- Government can resolve the market’s failure to build “missing middle” stock, either by directly providing public housing, or by providing incentives to suppliers and/or buyers (Cortright 2017, Thompson 2017)

- Reduce the home mortgage interest tax deduction by capping it at $500,000 instead of $1 million (Thompson 2017), so housing policy tilts less to the well-off and reduces current incentives to overbuild and sprawl (Quednau 2017, Distorted DNA 2016).

|

| Suburban sprawl has been incentivized by the mortgage interest deduction (Google screen capture) |

SOURCES

Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren and Lawrence Katz, "The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment," American Economic Review 106:4 (2016), 855-902

Joe

Cortright, “Why America Can’t Make Up Its Mind About Housing,” City Observatory, 16 May 2017

Matthew

Desmond, “How Homeownership Became the Engine of American Inequality,” New York Times Magazine, 9 May 2017,

MM48ff

Distorted DNA: The Impacts of Federal Housing Policy (Strong Towns, 2016)

Distorted DNA: The Impacts of Federal Housing Policy (Strong Towns, 2016)

Ewald Engelen, Sukhdev Johal, Angelo Salento and Karel Williams, "How to Build a Fairer City," The Guardian, 24 September 2014

Ryan Holeywell, "How the 'Missing Middle' Can Make Neighborhoods More Walkable," Urban Edge, 29 March 2016

Elizabeth Kneebone, Carey Nadeau and Alan Berube, "The Re-emergence of Concentrated Poverty: Metropolitan Trends in the 2000s" (Brookings Institution, 2011)

Jens Ludwig, "Moving to Opportunity: The Effects of Concentrated Poverty on the Poor," Third Way, 22 August 2014

Ryan Holeywell, "How the 'Missing Middle' Can Make Neighborhoods More Walkable," Urban Edge, 29 March 2016

Elizabeth Kneebone, Carey Nadeau and Alan Berube, "The Re-emergence of Concentrated Poverty: Metropolitan Trends in the 2000s" (Brookings Institution, 2011)

Jens Ludwig, "Moving to Opportunity: The Effects of Concentrated Poverty on the Poor," Third Way, 22 August 2014

Rachel

Quednau, “The Problem with the Mortgage Interest Deduction,” Strong Towns, 31 May 2017

Derek

Thompson, “The Shame of the Mortgage-Interest Deduction,” The Atlantic, 14 May 2017

No comments:

Post a Comment