|

| Claudia Rankine (Source: KCRW. Used without permission.) |

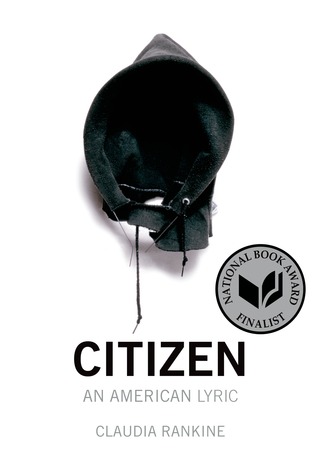

Poet Claudia Rankine, whose book Citizen was both a National Book Award Critics Circle winner and a New York Times best-seller, said she doesn't know whether we Americans can in the near future "get to a place where we respect other people's humanity." Her comment was part of her answer to a question at Thursday's nights talk in Coe College's Sinclair Auditorium. The questioner had mentioned an interracial date that drew stares in mid-1960s Chicago, and wondered whether his grandchildren would ever see society get to a stage where race isn't so present. She said racial difference was always apparent, so we'd never get to a truly "post-racial" destination. When she rephrased the question to "respect other people's humanity," she said she didn't know, but hoped so. She noted that evidence from history is ambiguous at best, and culture is hard to dismantle.

She drew a decent-sized crowd (200-300?), although in a large auditorium it looked small. She read for about 40 minutes, which included showing two videos she made with her husband, John Lucas. She took questions for about 30 minutes, after which there was a reception and book-signing in the lobby.

Rankine sees our contemporary racial situation--in his introduction, Professor Nick Twemlow referred to "a long, often fraught moment in our culture"--as a system, which black people were excluded from creating, but in which we are all now trapped. When a female student asked her how she managed not to be (or at least not to sound) angry, she said she wasn't angry at white people, even those "random" whites who act aggressively, but gets angry at the failures of, say, the justice system.

The book Citizen features elegantly written prose-poetry reflecting on how it is when race is not merely an issue to consider but an inescapable fact of life. Her writing excellently reveals the interior life of the mind. She makes clear that, even for the well-intentioned, race is a tangled web that will take maybe generations to unravel, if even then.

At Coe she read sections of her text without introductions, but did discuss some of the pictures in the book at some length.

The photograph of the "Jim Crow Rd." street sign on page 6 is a real sign, photographed by a friend of hers in Flowery Branch, Georgia. (I mapped it on my iPod during the talk; Flowery Branch is a suburb of Atlanta, near Gainesville GA.)

|

| (From Google maps, not the picture in the book) |

Urbanists will notice the large-lot subdivision with no sidewalks. Rankine noted that contemporary societal segregation "allows us to never have a person of another race in your home." One of the bases of urbanism is the expectation that the 21st century is going to prove that degree of separation an unaffordable luxury; that we're going to find ourselves in closer proximity; and we're going to have to learn how to live together, to converse and to hear each other's stories. She is not shy about telling those stories, either, which is her great contribution. She told another student that she had had to train herself to respond to micro-aggressions (such as she doggedly reports in Citizen) because otherwise she carries the situations with her and replay them and not sleep. Such responses are conversation, and progress might result. Just taking it silently changes nothing, except one's own blood pressure.

Much of her book details those micro-aggressions that are an unfortunate part of everyday life, even for a black university professor. (She's on the faculty at the University of Southern California.) Micro-aggressions aren't the physical violence and hate-filled screaming faced by pioneers like Jackie Robinson and James Meredith, or the marchers at Selma. They are more subtle, and might not even be fully-conscious. Sometimes they make the individual invisible, sometimes hyper-visible. Here's one that sticks with me, because of its seeming ordinariness:

When your waitress hands your friend the card she took from you, you laugh and ask what else her privilege gets her? Oh, my perfect life, she answers. Then you both are laughing so hard, everyone in the restaurant smiles. (p. 148)An honest mistake made by a harried worker? Perhaps. But Rankine told the audience this "happens to me quite frequently," and never in the reverse (i.e. the waitress hands her her white colleague's credit card). After awhile, either because you're living it, or because you're reading it, too much adds up for all these to be random accidents. Which shows we all have a long way to go.

The rain this morning pours from the gutters and everywhere else it is lost in the trees. You need your glasses to single out what you know is there because doubt is inexorable; you put on your glasses. The trees, their bark, their leaves, even the dead ones, are more vibrant wet. Yes, and it's raining. Each moment is like this--before it can be known, categorized as similar to another thing and dismissed, it has to be experienced, it has to be seen. What did he just say? Did she really just say that? Did I hear what I think I heard? Did that just come out of my mouth, his mouth, your mouth? The moment stinks. Still you want to stop looking at the trees. You want to walk out and stand among them. And as light as the rain seems, it still rains down on you. (p. 9)

SOURCE: Claudia Rankine, Citizen: An American Lyric (Graywolf, 2014)

SEE ALSO:

"Speakers Raise Tough Issues at Coe MLK Celebration," 19 January 2015

"The Latest Bad News and Our Common Life," 17 December 2014

"The Race Card Project," 12 February 2014

"Race Matters, Damn It," 16 April 2013

No comments:

Post a Comment