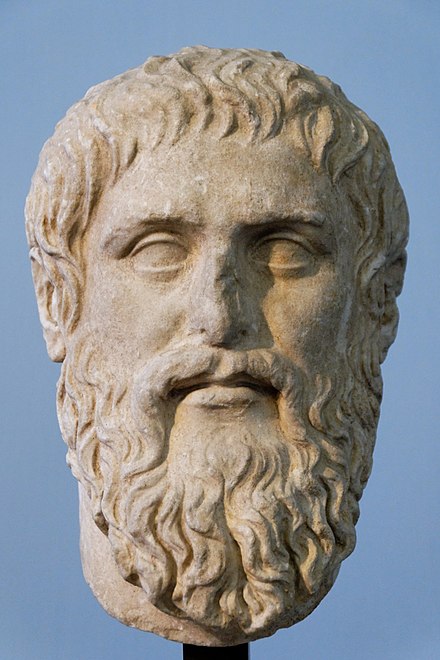

The topics they covered–the nature of democracy, its value, its vulnerabilities–are not new. You can find those in Plato’s Republic, which was written nearly 2400 years ago...

|

| In Book 8 of Plato's Republic (c. 380 BCE), he argues democracy descends to tyranny when the masses seek a powerful leader to advance their interests [Wikimedia commons] |

...and Sinclair Lewis’s novel You Can’t Happen Here, written in the depths of the Great Depression, argued America was not immune to the fascism then engulfing much of Europe.

What’s new in How Democracies Die is the sense of urgency, coupled with the notion that American democracy would go, not with a bang like the revolutions some imagined in the 1960s, but with a whimper after a long period of erosion. Levitsky and Ziblatt have subsequently published Tyranny of the Minority [Crown, 2023], extending the argument to concerns that anti-majoritarian features of the American constitution may enable regressive forces to obstruct the emergence of a truly multiracial democracy.

I’ve read How Democracies Die, and have taught it in my Contemporary Political Theory class at Coe College.

I have not read Tyranny of the Minority, which is too bad, because I think the arguments of the second book may have some interesting things to say to the arguments of the first book.

But I’ll stick to How Democracies Die in what follows, as well as drawing on other important contemporary works like Strong Democracy by Benjamin Barber [California, 1984/2004] and The Future of Freedom by Fareed Zakaria [Norton, 2003].

|

| Benjamin Barber (1939-2017) wrote extensively about "strong" democracy with more public participation and consensus-seeking |

I want to highlight two arguments in How Democracies Die that remain relevant for us, for the foreseeable future at least.

1. The first is that authoritarian regimes tend to insinuate themselves into democratic cultures, rather than immediately overpowering them. In chapter 4, the authors describe the small steps that led to autocracies at various times in places like Peru, Turkey, Venezuela, Russia, and Hungary:

Taking legally sanctioned steps in the name of some public objective

e.g. combating corruption or violent groups or economic crisis

“Capturing the referees,” including packing the courts and gaining control of law

enforcement

Sidelining key opponents through favors, false criminal charges, and/or lawsuits

Changing the rules of the game by reforming the constitution, electoral system,

and other institutions in ways that disadvantage or weaken the opposition…

again this can be done in the name of some unquestionable good like limiting

voter fraud

It can take many years, and a lot of this kind of insinuation, to get to the point where democracy exists only in name.

|

| Portland 2020: federal agents "restoring order in the streets" |

Anti-democratic statements are reprehensible in themselves, not to mention signs of bad judgment since a prospective leader ought to know better than to make them… but more importantly, they are warning signs of creeping authoritarianism that needs to be snuffed out before the real trouble begins. Levitsky and Ziblatt cite historical examples from Britain, Costa Rica, the United States, and other states where moderates successfully closed ranks across partisan divides to marginalize authoritarians.

|

| Marine Le Pen (b. 1968): She, like her father, has (so far) been kept from power in France by a coalition of elites [Wikimedia commons] |

Our authors highlight the lesson that political leaders across the spectrum need to take immediate alarm at authoritarian challengers, and to head them off right away. Elites need to react at once whenever would-be leaders reject in words or action the democratic rules of the game, deny the legitimacy of opponents, tolerate or encourage violence, and/or indicate a willingness to curtail the civil liberties of opponents or news media–especially when, in the case of Donald Trump since 2015, they do all of those things.

2. Which brings us to their second argument: that democracy is an absolute good. Most people in politics do politics in part to achieve some public policy changes. (Trump is an exception to this, but he is unusual in this and many other ways.) For myself I would cite things like economic opportunity that is equal and inclusive, sustainable development that limits the damage from pollution and climate change, an end to dependence on motor vehicles for transportation, and government financial responsibility.

What Levitsky and Ziblatt would yell in my ear is that maintaining democracy is at least as important as any of these, so I should resist all shortcuts to my happy place policy outcomes. Democracy is not just a means to these ends, it is a goal in itself.

|

| Would I trade democracy for better bike routes? Public housing? Climate change mitigation? |

Democracies, they stress in chapter 5, rely on the “thin tissue of convention” including strong democratic norms, mutual toleration, and restrained use of institutional prerogatives. These are the “guardrails” that protect democratic systems. Here their argument relates to Barber calling for active participation that goes beyond voting, and Zakaria insisting that majority rule without strong guardrails is a recipe for disaster.

Making democracy a priority starts with us, which is where things get tricky. Norms, inconveniently, are not fixed: Great Presidents like Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, and particularly Franklin Roosevelt took important actions in times of acknowledged emergencies in order to move America forward. In the process, norms of their times–about the role of the President and the scope of the federal government–were in shattered pieces everywhere. Lincoln famously said in response to calls for institutional forbearance that the Constitution is not a suicide pact. I think we’d mostly agree that he was right.

But norm-breaking also got us into Vietnam, Watergate, and destructive proxy wars in Central America. Recently, Presidents have used executive authority in ways that make me extremely uncomfortable, in the face of congressional paralysis. When Democrats controlled the House of Representatives, they removed some Republicans from committee assignments including the January 6 committee… for arguably good reasons, in cases like Marjorie Taylor Greene and Jim Jordan, but still contrary to norms.

|

| Congressional deadlock has led to unilateral executive action on immigration, student loan debt, health care, ... |

Putting their advice into practice gets even trickier when we live, as we do, in polarized times. Mutual toleration and institutional forbearance require a mutual trust that may no longer be possible, and may no longer be warranted. Which runs us into the argument of Tyranny of the Minority, the second book in the series. Constitutional reforms to make the Senate and House of Representatives more representative, and fixed terms for the Supreme Court, would arguably make the system more reflective of majority opinion, not to mention inclusive of a variety of perspectives. But at what cost to the system’s precious guardrails?

A Democratic Party with a diverse coalition faces some serious choices in the next several elections.

Do they make a priority of democracy, protecting the guardrails of the American political system? Or do they use it as a talking point against their clearly compromised opponents, seeking an electoral advantage that can deliver policy wins?

Do they put preservation of the American democratic system ahead of, say, national abortion rights or making the tax system more progressive or stricter environmental regulations?

Levitsky and Ziblatt in chapter 9 argue that making democracy an absolute value does not require giving up entirely on policy outcomes: They use the example of seeking economic measures that would benefit working class whites as well as, not instead of, blacks and other groups that have suffered discrimination. Redefine success as joint-gains (inclusive) rather than zero-sum, I think is their message.

|

| "Fixing health care" panel, May 2018: Are there joint-gains solutions to wicked problems? |

An approach to another policy conundrum might help illuminate their point: A housing policy that increases supply and lowers prices is going to have some seriously negative effects on households for whom their house is the lion’s share of their retirement savings. So we should also be about working on a retirement system that doesn’t rely on some people being un- or under-housed. (See Shane Phillips, The Affordable City: Strategies for Putting Housing Within Reach (and Keeping it There) (Island, 2020)).

It gets more difficult when we contemplate remedying past injustices.

I’ve become convinced over the years that opportunity in America is heavily conditioned on race, and that remedying that is going to require some reparations.

Making movement in America equitable, safe, and environmentally and fiscally sustainable is going to require getting a good bit of our land area back from motor vehicles.

Can we even imagine getting to either place while remaining true to all the safeguards of democracy commended by Levitsky and Ziblatt?

SEE ALSO: "Deliberation and the Shutdown," 3 October 2013

Theodore Johnson, "American Democracy is Fine. It's the Republic That's in Trouble," Washington Post, 23 May 2024