|

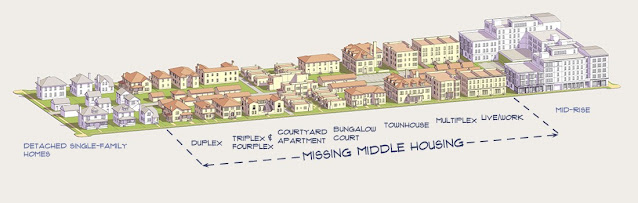

| What we're going to need more of (Swiped from Optikos Design Inc. via cnu.org) |

2021 U.S. Census estimates show continued slow growth for the State of Iowa. Cedar Rapids may be one of the best cities in America for millennials to get rich, but neither this designation by Money magazine nor our super-competitive housing prices have led to a stampede of Californians. In fact, the latest Census data show few stampedes anywhere away from cities, despite the potential for additional volatility during the pandemic, and despite prominent memes to the contrary (Frey 2021, Fry and Cohn 2021).

Cedar Rapids 2020 population was 137,710, up 9 percent from 2010, a touch higher than the 7.4 percent rise for the country as a whole. (2021 estimates are not available at this time.) Another 9 percent gain in the 2020s would get us to the neighborhood of 150,000, which is where a housing needs survey commissioned by the city has us; adding Marion and Hiawatha gets it over 200,000 (Maxfield Research 2020: 13). That assumes the same routine growth in the near-future as in the recent past, without any surge of in-migration (or sudden out-migration).

In the longer run, however, climate change may provide a greater impetus for people to move here than has our low cost of living. Iowa is not a Great Lakes state, but we can almost see them from our houses, and we share enough attributes with our neighbors that this statement by the Council of the Great Lakes Region might well apply to us: The bi-national Great Lakes mega-region, claims Council CEO Mark Fisher, which surrounds the largest freshwater in the world and is home to 107 million American and Canadians as well as a significant regional economy in North America, will be the destination of choice for many around the world who are seeking refuge from a rapidly changing climate and new economic opportunities.

"Receiver cities" are those places likely to receive climate-induced migration from regions plagued by increased incidence of floods, droughts, dangerous heat, and violent competition for resources. A panel at last spring's Congress for the New Urbanism conference focused on Buffalo and Cleveland, which are post-industrial cities that have lost a lot of population in the last half-century, and thus have an ideal combination of inexpensively available space in a traditionally-developed core. (Cleveland hit its peak city population of 914,808 in 1950, when most of the city would still have been traditionally-developed. The 2020 population is 59.2 percent below that, suggesting there's plenty of room for new arrivals.) Cedar Rapids has a history different from those of Buffalo, Cleveland, Flint, and Youngstown, but the city center is still building back from the 2008 flood, not to mention the out-migration of residents and businesses in the decades before that. So why not us?

Why not us? How I answer that question can vary from day to day, but that need not detain us here. It was a rhetorical question, anyway! According to Robert Steuteville, editor of CNU's journal Public Square, there are ways cities can prepare for a potential influx of climate refugees (Steuteville 2021). Fortunately, since we can't predict whether or when or how large this influx will be, the CNU approach is designed not to develop acres and acres of empty space, but will improve service to current residents as well. It's like Strong Towns says...

Here are Steuteville's eight recommendations:

- Build more sustainably, including enabling car-free living. Nicole Dieker (2019), who moved here from Seattle, managed car-free at least for awhile, but it was more work than most people are able to do, particularly when you can get anywhere in town by car in 15 minutes. Bike infrastructure is improving, but public transportation has circuitous routes and limited hours of operation. The Urban Transitions website argues even more greenhouse gas emissions can be averted through changes in building.

- Focus on the "missing middle" to grow population in existing neighborhoods. The Cedar Rapids City Council just authorized accessory dwelling units by right in all areas of the city (Payne 2021). This is an important step, but most important in the center of the city, which has the greatest potential for sustainability, walkability, urban living, or whatever you care to call it.

- Bring downtown back, with mixed-used buildings to add residents and businesses. The new construction in the "Banjo Block" on 4th Avenue SE, which will add 224 new apartments on a former brownfield area (Green 2020), is a huge addition. So are the 110 units planned for New Bo Lofts south of Geonetric. We need to figure out a way to liberate valuable land that's not being used, such as in the 1200 block of 2nd Avenue SE, and the 1000 block of 3rd Street SE. I would look strongly at a land value tax. I'd also like to talk the MedQuarter out of the vast wasteland they're creating between downtown and Wellington Heights.

- Convert single-use commercial corridors to mixed use. Are we talking about Collins Road? Or Wiley Boulevard? I don't think so... they're too far gone to do cost-efficient sprawl repair, and too far away from the center to be much help. There are some interesting developments on the west side, on 1st Avenue and Ellis Boulevard, for example. I'd like to see more of this on 6th Street West, 1st Avenue East, and maybe other strips close to the core.

- Be competitive rather than waiting for the seekers of cheap dry land to find you. A month ago I wrote the calls for change by mayoral candidates Amara Andrews and eventual winner Tiffany O'Donnell were "refreshing in a town where the political culture can be maddeningly complacent." Changes should consider future residents, who will be different from current residents, and why they should move here and not Duluth.

- Tear down unnecessary freeways as Rochester NY and Milwaukee already have done. Shall we talk about this? The Gazette had a brilliant long article Sunday on the destruction of the Little Mexico neighborhood in the 1960s to make room for I-380 (Jordan 2021a), and in the 1990s my student Darcie Carsner did an honors thesis on how the route was plowed through the western end of Czech Village (Carsner 1996). There were neighborhoods then... they could be neighborhoods again! Counterpoint: Iowa Department of Transportation planner Cathy Cutler justified widening the highway on the grounds that "People are uncomfortable on 380 at four lanes. That's why we're expanding to six lanes" (Jordan 2021b). So we're going to be limited by what makes drivers "uncomfortable?!"

- Reform zoning to allow #1-6. Cedar Rapids has taken some important first steps; besides allowing accessory dwelling units, we have adopted a form-based code and revised or eliminated parking minima.

- Implement a walkability plan, correcting decades of auto-centric engineering. Cedar Rapids adopted a pedestrian master plan in December 2019, which you can find here. It contains 18 policy strategies aimed at developing [1] "a connected pedestrian network that links popular destinations year-round" and [2] "a culture of walking." There are some interesting proposals for more sidewalks and better promotion of the benefits of walking, but in terms of what Steuteville identifies as needing undoing--"one-way streets, excessively wide lanes, turn lanes, too little pedestrian space, and other design factors"--we've made a good start. The vast majority of our one-way pairs have been restored to two-way traffic.

|

| Before (Google Maps screenshot from 2008) |

SEE ALSO

Lavea Brachman and Eli Byerly-Duke, "Legacy Cities Can Think Big for Transformative Impact with ARP Funds," The Avenue (Brookings), 12 October 2021

Darcie Carsner, Ethnicity in American Political Participation: The Case of the Czech Village (Coe College, 1996)

Maxfield Research and Consulting, "Comprehensive Housing Needs Update: City of Cedar Rapids, Iowa," February 2020

Robert Steuteville, "Eight Ways for 'Receiver Cities' to Prepare," Public Square: A CNU Journal, 9 December 2021