|

| (Source: Wikimedia commons) |

Senator Ben Sasse (R-Nebraska) has a new book out, subtitled "Why We Hate Each Other--and How to Heal." Three weeks before the midterm elections, Sasse seems to be speaking to a weariness in at least some corners of America with the fraught, angry, tribal nature of our national politics. Perhaps, reader, you are one of the weary ones? I certainly am, being the sensitive sort who readily relates to the Framers' concern with the "tumults and disorders" that surround elections. Or perhaps you enjoy being angry? A few years ago, a Cedar Rapids activist allowed, "I have low blood pressure. When I get mad, I feel good." The problem for me is, these days election campaigns are always going on, especially though not only because President Trump is a bottomless well of offensive inflammatory remarks. He is a symptom, not a cause, of our present discontents.

A colleague walked into my office yesterday, observing that people on the left and the right are contributing to the public anger. At that time I rose to the shiny lure of "false equivalence," but I think if we're going to be productive here we need to jump quickly past the assignment of blame. Besides, to some degree anyway, he's right (Frenkel 2008).

Maybe I'm besotted with economics, but I think a good way to start understanding people's actions is to look for the incentives that drive them. Politicians, whose career success depends on winning elections, will take the stances and pursue the measures that will get them comfortably reelected; if they don't they are likely to be replaced by somebody who does that better. In the 1970s and 1980s, we used to think that mostly meant competing with the other party for the majority of the public in the center of the political spectrum. But as voters have sorted themselves ideologically--they're typically all left or all right on a wide range of seemingly-unrelated issues--there's less of a middle to compete for. (Voters have also sorted themselves geographically, so individual representatives often come from more politically homogeneous districts, and so their main danger is not from the center but from within their own party... so their electoral incentives are against compromise.) In a bipolar political universe, you try to rally your base, and you fear the other side's base. Besides, strong emotional appeals are more likely to encourage donations and volunteering, which are the vital forces of any competitive campaign. (See R. Kenneth Godwin, One Billion Dollars of Influence [Chatham House, 1988], ch. 3).

Whichever came first, the polarized public or polarizing politicians, they have a reinforcing effect on each other. The red meat that Party A rationally throws to its base is going to anger followers of Party B, and provide them greater amounts of their own red meat. Those who remain in the center, those who once provided a moderating influence in politics and government, are either leaving in disgust, or choosing the "lesser of two evils" and contributing to the success of the extremists of either Party A or Party B. News media and websites, following the examples of the interest groups Godwin studied, find market niches by appealing to strong partisans with more partisan appeals. This too contributes to the roaring bonfire of public anger.

What I'm describing, with my dime-store game theory, is a political world where anger pays and moderation does not, with the byproduct being increasing levels of anger on both sides. Think of an alternative where a player can choose an uncooperative strategy with a 50% chance of complete success and a 50% chance of complete failure, or a cooperative strategy with a higher chance of partial success--say, 75% chance of 75% success. (Obviously, I'm making these numbers up.) Based on expected value, you'd choose the cooperative success unless you estimated the chance of partial success with the cooperative strategy even slightly lower--say, 70% chance of 70% success. Or if we added another rule whereby the uncooperative had unlimited chances to play and the cooperative had to quit after one turn.

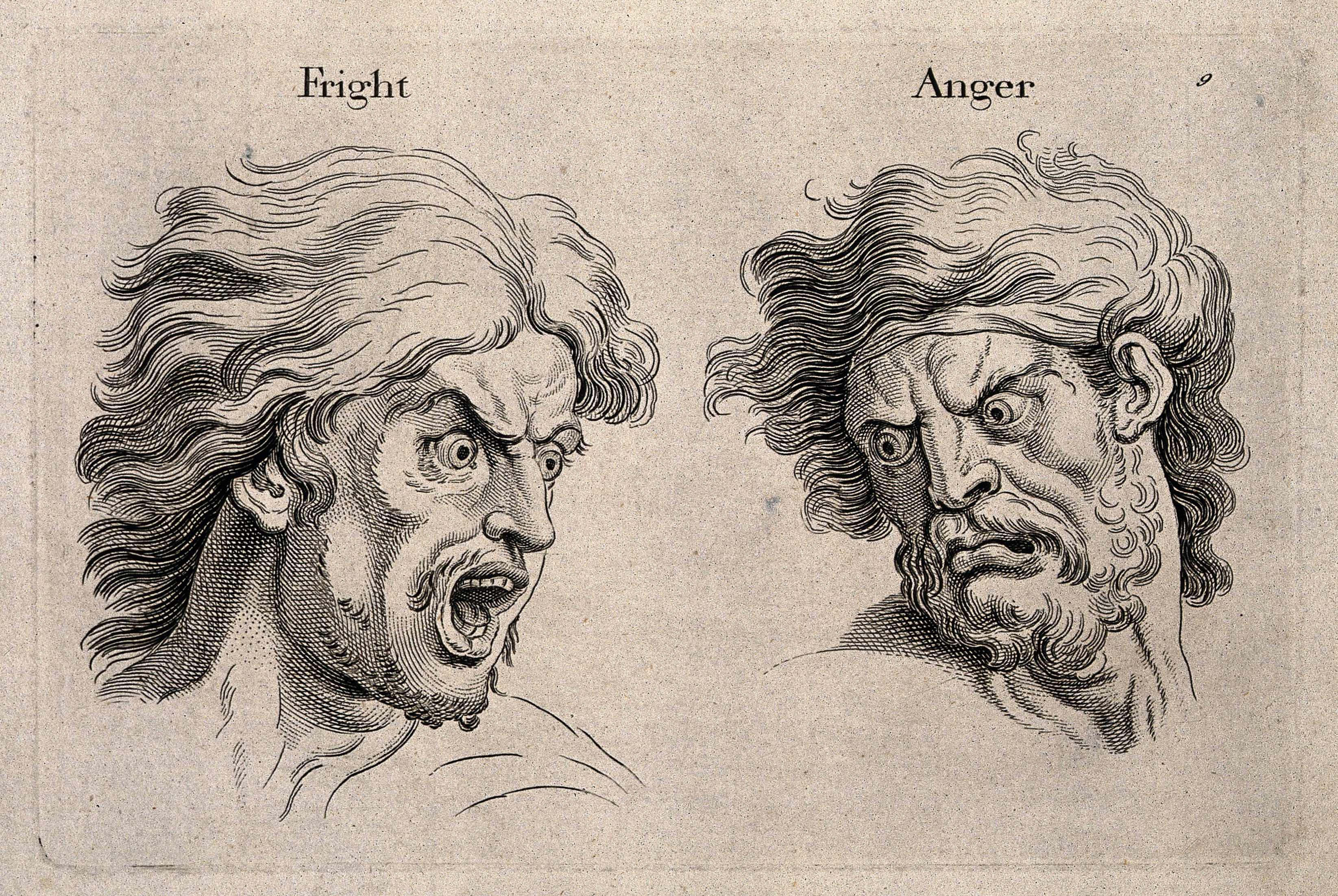

| (Source: totalmedia.co.uk) |

Is anyone, in this sort of world, likely to be constrained in their statements and actions? Could there possibly be incentives to counteract those which are provoking ever-higher levels of anger?

The country has, occasionally, come together in recent years, most memorably after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Bipartisan coalitions in Congress have formed around certain necessary actions, like economic stimulus during the 2008 recession, or avoiding government shutdowns. But these were momentary emergencies, and the impulses to cooperation proved short-lived. My sense is the default state of political affairs, even in these times of great uncertainty, is going to be laden with anger, stoked by partisan rivalry.

Alan I. Abramowitz of Emory University, whose book The Disappearing Center (Yale University Press, 2010) is as good an account of political polarization as any, concluded that partisan-ideological polarization is not going away any time soon.... Even if efforts at bipartisanship are sincere and not mere window dressing, the differences between the two parties on almost every major domestic and foreign policy issue are so great and the numbers of moderates in both parties are so small that reaching any agreement will be almost impossible (p. 169). Given that, the more direct route for either party to achieving its policy goals is to win unified control of the Presidency and Congress. Given how nationally competitive the parties are nationally, this prospect is always within reach for both Democrats and Republicans. Case in point: Republicans control the Presidency and Congress today, but Democrats have designs on capturing the House next month, and think about how little would have had to change in 2016 for Democrats already to have control of the rest. This alone motivates both sides to gin up their respective bases, which raises everyone's blood pressure.

Once in control of the levers of government, the prospect of losing control is always just around the corner, too. So the incentive is to act quickly around issues that unify the base, rather than working to achieve common solutions.

If there is hope from either side to lead us out of this vortex of anger, it would probably have to come from the Democrats. (Bear with me here--I'm not just being partisan!!) Republicans are heavily invested in President Trump, vicious rhetoric and reckless disregard for the truth notwithstanding. Moreover, Democrats are the "party of government," in domestic policy at least, so have more to lose when government doesn't work.

It is pleasant to imagine a Democratic President in 2021, using their position to lead the country back together. They could seek policies on issues of common concern; offer policy concessions to Republicans; and include members of the opposition in key appointments. But President Obama did all these things, and look where it got him--and the body politic. It's easy to imagine additional items Obama might have pursued--malpractice reform in the Affordable Care Act, for example--but it's hard to think of successful approaches to national leadership that haven't already been tried.

I think we're stuck with this situation for a long time. Eventually something may come along that really shakes things up. That will bring its own trauma, of course. In the meantime, individuals are best advised to do what they can to avoid the crazy, and to avoid adding to it.

SEE ALSO:

Elizabeth Bruenig, "The Left and Right Cry Out for Civility, But Maybe That's Asking for Too Much," Washington Post, 16 October 2018: similar topic and worth a read, though it addresses public expression rather than public attitudes

"What's the Matter with Congress?" Holy Mountain, 30 May 2013: review essay of recent works on political polarization.

| (Source: themindfulword.org) |