The mechanics of climate change are pretty well understood: human industrial activity puts more carbon and methane and stuff into the atmosphere, where they are now concentrated to an extent unseen in history. This means something, although drilling down to exactly what it means is frustrating. In the decades since this idea was first publicly broached, data have accumulated that are mostly consistent with initial warnings: melting polar ice caps, rising global average temperatures, more severe weather events like hurricanes, floods and droughts. Climate models suggest whatever's been happening is not going to stop where we are now, but rather that what's been happening has been a small preview of an increasingly weird future.

This would seem to enough information to consider some mitigating action to be prudent if not an outright moral imperative, but moral imperatives are difficult without economic imperatives to go along with them. Where I'm writing, energy and land prices are considered cheap, so climate action has understandably been a hard political sell.

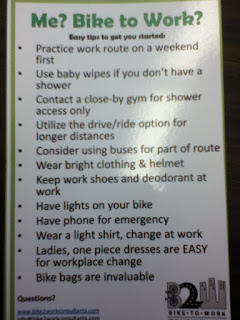

|

| This sign does not say "Time to use less energy" |

These numbers exist in spite of considerable political obfuscation as well. While Trump fiddles with the trigger mechanism before he shoots the Paris agreement, Iowans got a rather strange perspective on the subject from state climatologist Harry Hillaker, who was interviewed last week by the Gazette's Erin Jordan. Hillaker works for the Iowa Department of Agriculture, and has been in his position 28 years; the Climatology Bureau he heads mainly compiles historical temperature and precipitation data for farmers. He may be more used to inquiries about soil moisture or what kind of summer it's going to be than about climate change, but seemed unprepared for her question.

Q: Do you believe climate change is happening?

A: It’s a thing that is always changing. The hard part is figuring out how much and in what ways and what causes it.Perpetual climate change may well be true, but there's incremental change and there's wholesale change. Hillaker sounds more like our Republican politicians (U.S. Senator Joni Ernst, at Coe this spring for a public event, said "the climate's been changing for a thousand years") than someone who has an informed opinion on five decades of climate change research. The undaunted reporter then asked "How much do humans factor into climate change?" Offered the opportunity either to explain the research on climate change, or to express skepticism about it, Hillaker responded that "Land use changes can have quite a large impact on resulting weather," and widespread planting of corn and soybeans in the state may be why we don't see as many 100 degree days as we used to. That information is not without interest, and frankly is new to me, but to say the least, an opportunity for public education on a widely-debated and arguably important issue was missed. Here's one guy who can opine with authority on whether we can continue to drive SUVs and eat lots of beef and build more highways and subdivisions without destroying life on Earth, and he takes the pitch like Casey at the Bat. Am I expecting too much?

Mitigating climate change is, ultimately, an international problem, because the scale of the climate is international. I don't have to breathe Shanghai's air or live without civil liberties, but we live on one planet (where the question of whether Iowa will break triple digits this summer is of minor importance). Besides, there's too much incentive for any country to allow others to do the heavy lifting on climate while it joneses short-term economic growth. However, as Benjamin Barber notes in If Mayors Ruled the World, a number of major cities are making their own climate mitigation efforts. This shouldn't be too surprising, because (a) many cities are located near large bodies of water and so will be vulnerable to rising sea levels, and (b) at least in America, urban political cultures have been far more pragmatic than states or the national government. Moreover, cities have at least some potential for effective action, because they account for such a huge proportion of economic activity. (In America, 20 percent of counties account for more than 2/3 of gross domestic product.) CityLab blogger Laura Bliss suggests cities have the capacity and the pull to mitigate climate change by:

- promoting transit-oriented development

- improving public transportation

- pushing buildings to become more energy-efficient

- getting drivers to pay more of the social cost of driving

- investing in renewable energy and electric vehicles (see also Roberts and Chretien)

NOTE: I first addressed climate change in this post from August 2013, which includes some basic sources. For other posts on this topic, please click "environment" under the list of labels in the column on the right.

SOURCES

Benjamin R. Barber, If Mayors Ruled the World: Dysfunctional Nations, Rising Cities (Yale University Press, 2013)

Laura Bliss, "5 Ways U.S. Cities Can Fight Climate Change Without the Paris Accord," CityLab, 31 May 2017

Elizabeth Daigneau, "Will States Stop Cities from Combating Climate Change?" Governing, January 2017

William A. Galston, "Paris Enjoys More Support Than Donald Trump," FixGov, 31 May 2017

Erin Jordan, "Iowa Land Use Influences Climate, State Climatologist Says," Cedar Rapids Gazette, 21 May 2017

Lori Riverstone-Newell, "The Rise of State Preemption Laws in Response to Local Policy Innovation," Publius 47:2 (Spring 2017)

Timmons Roberts and Larry Chretien, "It'll Take More Than a Hybrid: Transportation is Moving to Electric Cars, Just in Time," PlanetPolicy, 26 May 2017

"Webinar--Municipal Issues in an Era of Preemption," Stateside, 2 March 2017

"What Happens if the U.S. Withdraws from the Paris Climate Agreement?", CBS.com, 27 May 2017

SEE ALSO:

Andrew Revkin, "For Climate Cause, Trump's Withdrawal from Paris Accord Just One Hurdle Among Many," ProPublica, 2 June 2017

Timmons Roberts, "Trump Dumps Paris: Now What?" PlanetPolicy, 1 June 2017

Pam Wright, "Trump Pulls U.S. Out of Paris Climate Agreement," The Weather Channel, 1 June 2017