As a first pass, this is brilliant, though as I shall suggest I think there are some other aspects of sacred space he doesn't discuss. Here are Stump's seven forms of sacred space:

(1) cosmic, elements of the universe, tangible (earth) and imagined (heaven)

("Doggie Heaven," swiped from fortheloveofhistruth.com)

(2) holy lands, territory that is significant because of its role in defining the group, usually though not always in terms of its traditional history, such as the land God promised to Abraham in Genesis 12

(Biblical "Land of Israel," from Wikipedia Commons)

(3) natural spaces, where the supernatural power is reflected in nature in some meaningful way, especially but not exclusively by animists and polytheists... Doesn't this look like a fun read?

(4) sacred cities, which are significant by association with key events (Mecca, Bethlehem), sacred figures, rituals, pilgrimages (Santiago de Compostela) or religious organization (Rome)

(Santiago de Compostela, Spain, from Wikipedia Commons)

(5) ordinary local spaces, churches, synagogues, mosques and other humanly constructed places of worship associated with the everyday practices including communal worship and many other functions

|

| Former location of Mt. Zion Baptist Church, Cedar Rapids |

(6) unique local spaces, same as above but applying to those with special association with central functions (the Great Mosque of Mecca, St. Peter's in Rome), sacred events (Lourdes) or relics

(Temple of the Sacred Tooth, Kandy, Sri Lanka, swiped from en.wikipedia.org)

(7) microscales, sacred objects such as icons, altars, or in some cases bodies

(Our Mother of Sorrows Grotto, Mt Mercy University, Cedar Rapids,

swiped from www.mtmercy.edu)

|

| Altar and Re table, Lovely Lane United Methodist Church, Cedar Rapids |

Stump's book focuses on religious groups, particularly Christianity, Islam and Judaism, and given that's quite a large chunk to bite off, it is a prodigious work. Nevertheless, by doing this he mostly overlooks (except for the discussion of microscales) the individual's relationship to the sacred. I would say that besides personal shrines, individuals may experience three types of sacred space.

First, there are places where one feels the presence of God (or ultimate reality, or whatever is your preferred term). This is different from saying places where God is present, because all western religions believe God is omnipresent. Though God may be "a very present help in trouble," it is usually quiet places where we sense God's presence. Perhaps quiet liberates our mind to wonder at Creation. During a troubled summer in Louisiana, I was shocked back to myself one morning upon seeing the sunrise through the trees near my apartment. Also, quiet, particularly in natural places, allows us to notice God instead of whatever might be stressing us. Here we can, in the words of John Denver's great song, "Talk to God and listen to the casual reply."

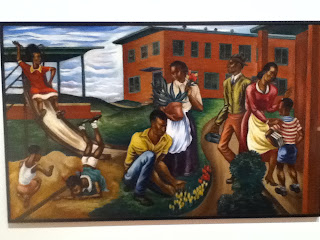

Another place we encounter the supernatural is in a beloved community. This is for me far more likely to be the case than when I "come to the garden alone," because I'm not a particularly spiritual person. I also generally don't like meetings. But at some times with some groups of people I feel a sense of the transcendent. When I discussed this with my Sunday school class, my friend Margaret mentioned the song "Betty's Diner" by Carrie Newcomer. The song describes the various hurts and frustrations of the diner patrons, but somehow together they find a caring community that brings out their own better selves:

First, there are places where one feels the presence of God (or ultimate reality, or whatever is your preferred term). This is different from saying places where God is present, because all western religions believe God is omnipresent. Though God may be "a very present help in trouble," it is usually quiet places where we sense God's presence. Perhaps quiet liberates our mind to wonder at Creation. During a troubled summer in Louisiana, I was shocked back to myself one morning upon seeing the sunrise through the trees near my apartment. Also, quiet, particularly in natural places, allows us to notice God instead of whatever might be stressing us. Here we can, in the words of John Denver's great song, "Talk to God and listen to the casual reply."

Another place we encounter the supernatural is in a beloved community. This is for me far more likely to be the case than when I "come to the garden alone," because I'm not a particularly spiritual person. I also generally don't like meetings. But at some times with some groups of people I feel a sense of the transcendent. When I discussed this with my Sunday school class, my friend Margaret mentioned the song "Betty's Diner" by Carrie Newcomer. The song describes the various hurts and frustrations of the diner patrons, but somehow together they find a caring community that brings out their own better selves:

Here we are all in one place

The wants and wounds of the human race

Despair and hope sit face to face...

Interestingly, the song does not mention God or any other spirit. It is clear, though, from Newcomer's corpus of songs that spiritual concerns are at the core of her songwriting, and so reasonable to infer a sense of spirituality in this community as well. And then there's the bridge:

You never know who'll be your witness

You never know who grants forgiveness

Look to heaven or sit with us

A third type of sacred place that relates to individuals is a place that is or should be inviolate. This may or may not be your church. Several congregations in Cedar Rapids have moved in recent years, including Buffalo United Methodist, Central Park Presbyterian, Maranatha Bible Church, People's Church and St. Mark's Lutheran. Still I read sad stories about churches closing, so I know it happens. But individual attachment to places that reaches the level of sanctity is hard to predict. There was much fuss in 2002 when construction of our town's new baseball required moving the veterans' memorial, and the local preservationist group Save CR Heritage formed in part in response to the destruction of two historic downtown church buildings. And Chicago media are full of public concern that the new Cubs' ownership may alter Wrigley Field in some way, or even--quelle horreur!--move the Cubs to the suburbs. I frankly don't know how much of this relates to sacredness and how much relates to other concerns. And I'm having trouble coming up with personal examples, too. If my church moved out of our roughly 50-year-old building, I don't think I'd mind, but if development threatened the Sac and Fox Trail there'd be blood in my eye.

(Demolition of First Christian Church, Cedar Rapids, May 2012,

swiped from savecrheritage.org)

Another dimension altogether is the effort of religious institutions to create a sense of sacredness in their worship space. That seems worthy of a separate post.