Sunday, March 27, 2016

Another vulnerability in the suburban development pattern

42nd Street NE in Cedar Rapids is undergoing some badly needed reconstruction this spring and summer. The street is down to one westbound lane from the exit off I-380 to Wenig Road.

The street in this 0.6 mile stretch is residential, with most houses built between 1955 and 1960, so it's not a stretch to guess the street is about 60 years old and this is the first reconstruction of this magnitude. There are, besides the houses, two schools: Pierce Elementary School one block east of Wenig...

...and Kennedy High School at Wenig and 42nd. (Kennedy's baseball field, not pictured here, was featured in the first game scene of the movie "The Final Season.")

Beginning with Lovely Lane United Methodist Church across Wenig from Kennedy, there are a number of churches along 42nd as well. Except for Lovely Lane, all are out of the construction zone, but their members normally would use 42nd for access from the east.

Average daily traffic count for 42nd is 14000 directly west of I-380; 11000 closer to Wenig; and 8600 west of Wenig.

The project involves a thorough resurfacing; while they're at it, they're widening the road slightly in order to add bike lanes. But the bike lanes are merely piggy-backing on the road reconstruction which is badly overdue. There are potholes. James Muench, assistant principal at Kennedy High School, told the Cedar Rapids Gazette it was "pothole city."

This is not a complaint about construction. Roads wear out, just like everything else in nature, and need replacing. The problem is that 42nd is designed to be THE arterial for this area. While it is being repaired there are no nearby alternative routes. To both the north and south of 42nd are residential subdivisions with no through streets. The nearest parallel through street is Collins Road, 0.6 miles to the north, but it's limited access and doesn't intersect with any north-south streets for an impractically long way. South of 42nd the nearest alternative is Glass Road, nearly a mile away--serviceable enough, but the only connection is via Wenig, a narrow winding hilly street that normally carries 1640 cars per day and has a 25 mph speed limit (and no sidewalks).

This isn't a life-and-death crisis, and I'm not trying to make it one. But having designed neighborhoods with only one route in or out certainly creates problems when we confront the inevitability of maintenance.

SEE ALSO:

City press release on construction schedule, http://www.cedar-rapids.org/city-news/media-releases/Lists/Releases%20and%20News/DispForm.aspx?ID=3810

B.A. Morelli, "'Pothole City' 42nd Street Getting Major Makeover," Cedar Rapids Gazette, 3 March 2016, http://www.thegazette.com/subject/news/government/pothole-city-42nd-street-getting-major-makeover-20160303

Saturday, March 19, 2016

Maple syrup festival 2016

March in Cedar Rapids means it's maple syrup time at the Indian Creek Nature Center! To say that this is a much-anticipated event in our community may underestimate the case. Cars were lined up along Bertram Road by the time we got there this morning.

Volunteers were hard at work directing traffic, making pancakes...

...and demonstrating traditional crafts.

The syrup for your pancakes came from sap from maple trees at the nature center. The sap started running early this year, explained our guide, but then it got too warm in March and it stopped running. He said tappers took about 5 percent of the sap from each tree, so it's sustainable. (Take too much and the tree will die, see.)

So today the vats just had water boiling in them, for ambience. The syruping totals for this year:

The syrup we had on our pancakes, then, was not only delicious but precious. If you wanted seconds, and I did, you went to Glenn.

We were kept company not only by our fellow townspeople of all ages, but by the nature center's numerous displays...

...and a jazz combo that defied all stereotypes and joined us early on this Saturday morning. (Behind them is a map of the Cedar River watershed.)

While enjoying good fellowship in a place that celebrates our connection to nature, I was reminded that an advantage of the compact urban form this blog keeps promoting is that it leaves more room for natural spaces. Suburban sprawl crowds out natural spaces. If you want to live close to nature, paradoxical as it may seem, live in a city and help others to do so.

This was not only the 33rd annual Maple Syrup Festival at Indian Creek, it was the final one in the round barn that has served that nature center for decades. Work is well along on the "Amazing Space" that will serve as the nature center's new home soon.

What will happen with their old building is up in the air. Development assistant Nancy Lackner told me the building is owned by the City of Cedar Rapids, so it's theirs to dispose of. There's been talk of a bike shed (the Sac and Fox Trail runs close by) or a demonstration farm, but nothing definite. I'm sure the right decision will be made when the time comes, but I've attended so many programs and eaten so many pancakes in this old barn I'd like to go back and see it every now and then.

|

| The barn as barn; from indiancreeknaturecenter.org |

SEE ALSO: Cindy Hadish, "Last Maple Syrup Festival in Indian Creek Nature Center Barn," Homegrown Iowan, 18 March 2016

PREVIOUS POSTS

"Groundbreaking at Indian Creek's Amazing Space," 1 August 2015

"Maple Syrup Time!" 22 March 2015

"Maple Syrup Festival," 1 March 2014

Wednesday, March 9, 2016

Cedar Rapids named Blue Zones community

The City of Cedar Rapids celebrated its designation as a Blue Zones Community yesterday evening with a gala celebration at the Downtown YMCA. Mayor Ron Corbett, along with representatives from the Blue Zones organization and Wellmark Blue Cross Blue Shield (which spearheaded the initial efforts), spoke at a brief ceremony.

Mayor Corbett, in recognizing participating volunteers from the community, praised the "grass-roots efforts" that led to the city's achievement. He noted "It was never meant to be a top-down effort," and promised "This is really just the beginning" of efforts to promote health and happiness. He pointed out Cedar Rapids is the largest city in Iowa with a Blue Zones designation. In your face, Des Moines.

Community organizations representing the nine Blue Zones ideals were located at stations around the gym and racquetball courts. Groups ranged from medical offices to churches to social services. Here, Taylor Bergen chats up visitors about the Ultimate Frisbee team:

Hy-Vee, all seven of whose Cedar Rapids grocery stores have achieved Blue Zones designations, offered healthy snack samples and hosted cooking demonstrations.

There were demonstrations of fun ways to get moving, in which attendees enthusiastically joined.

All told, it was an impressive mobilization of community organizations.

By now, 56 worksites, 36 restaurants, and 18 schools have fulfilled the requirements for Blue Zones designation. 22000 individuals have made some level of commitment to attaining Blue Zones goals. The impacts can be seen in new ways (which are actually older ways) of thinking about how we design our cities, and the kinds of food we choose and offer to others. It seems to be having an effect on how people think about community as well, which is all to the good.

EARLIER POSTS

"Am I Blue," 4 June 2013

"Dan Burden on Sidewalks and the Future," 13 December 2015

Monday, March 7, 2016

What is a form-based code? and other mysteries of zoning

|

| Zoning map from 1920s Winnipeg (Source: Wikimedia commons) |

One of the forces that has gotten us into the fix we're in--sprawl-wise and society-wise--is single-use (Euclidean) zoning, which originated over a hundred years ago with the idea of keeping polluting and noisome businesses (factories, slaughterhouses) well separated from where people were trying to live and raise children and such. I don't want to live next to a smokestack anymore than you do, nor do I want to live next to a slaughterhouse, nor when it comes right down to it a baseball stadium or an amusement park. So far, so good.

This laudable beginning, however, led to more dubious efforts to classify and separate. As Andres Duany and his co-authors explain:

This segregation, once applied only to incompatible uses, is now applied to every use. A typical contemporary zoning code has several dozen land-use designations; not only is housing separated from industry but low-density housing is separated from medium-density housing, which is separated from high-density housing. Medical offices are separated from general offices, which are in turn separated from restaurants and shopping. (2000: 10)Local zoning laws, long helped by federal housing policies, have contributed to the state of the American landscape that is familiar to nearly everyone reading this: large-lot subdivisions located from far from anything anyone does; shopping malls and strips on congested roads; much of the day spent in motor vehicles, stuck in traffic jams or running errands in "Mom's taxi;" a vast sea of parking lots; inner city slums isolated from productive places; the gradual disappearance of third places; and financially-pressed cities and states scrambling to keep up with it all.

Nowadays we know a lot about how these systems work. The public may not be pushing for change: there's a tendency to regard this landscape and the burdens it places as part of the natural order of things, and those with a disproportionate share of economic and political clout may well be glad to be well away from everyone else with all their problems. Duany et al. note: "It has been well documented by Robert Fishman and others how racism was a large factor in the disappearance of the middle class from the center city ("white flight"), and how zoning law clearly manifests the desire to keep away what one has left behind" (2000: 11n).

But there are signs of change. Younger people are showing more interest in urban living, and city governments want to make their places both more appealing and more financially-solvent. Now the same zoning codes which were used to sell development are seen as obstacles. Their rigid rules and formulae restrict individual choice and community adaptation. Whatever to do?

One trend is to wider use of form-based codes. The Form-Based Codes Institute, a non-profit planning organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., defines this concept as

a land development regulation that fosters predictable built results and a high-quality public realm by using physical form (rather than separation of uses) as the organizing principle for the code. A form-based code is a regulation, not a mere guideline, adopted into city, town, or county law. A form-based code offers a powerful alternative to conventional zoning regulation.In other words, a form-based code focuses on outcomes like the look and feel of a place, rather than on what goes on there. Of course, a community could decide that it prefers the look and feel of a large-lot subdivision, but presumably the motivation to adopt a form-based code would be to seek to achieve an integrated vision not possible with single-use zoning. Cincinnati, Ohio, whose code won an honorable mention from the organization in 2014, provides for a city-wide network of walkable neighborhoods, with standards for building and frontage types, based on the transect (see below), but encouraging neighborhoods to produce their own plans. More recently, three first-ring suburbs of Chicago collaborated on form-based building standards for Roosevelt Road, a highway that runs through all three. In a 1.5-mile stretch, there are pedestrian zones and transitional zones, as well as an auto-oriented zone close to Harlem Avenue, but all emphasize pedestrian safety:

|

| Roosevelt Road form-based code (swiped from formbasedcodes.org) |

The FBCI sites includes examples of codes, webinars and opportunities to register for more intensive conferences.

Communities can consider the natural flow of the transect, which is one way that a form-based code can be organized. The transect is a series of gradual transitions from open/rural spaces to the dense urban center, intended to model a natural transition from, say, seafront to forest. The zones are based on character, form and intensity of development. Basing city zoning on this concept is intended to "provide the basis for real neighborhood structure, which requires walkable streets, mixed use, transportation options, and housing diversity," instead of forcing people to drive great distances to get to separated uses. "The T-zones are intended to be balanced within a neighborhood structure based on pedestrian sheds (walksheds), so that even T-3 residents may walk to different habitats, such as a main street, civic space, or agrarian land."

| Source: Center for Applied Transect Studies |

The Center for Applied Transect Studies website includes model transect-based codes and modules, as well as--particularly useful for non-planners like me--a photo gallery of examples from the different T-zones. While CATS focuses on municipal zoning, I think this concept would be more relevant to metropolitan regions where there still are natural and rural zones.

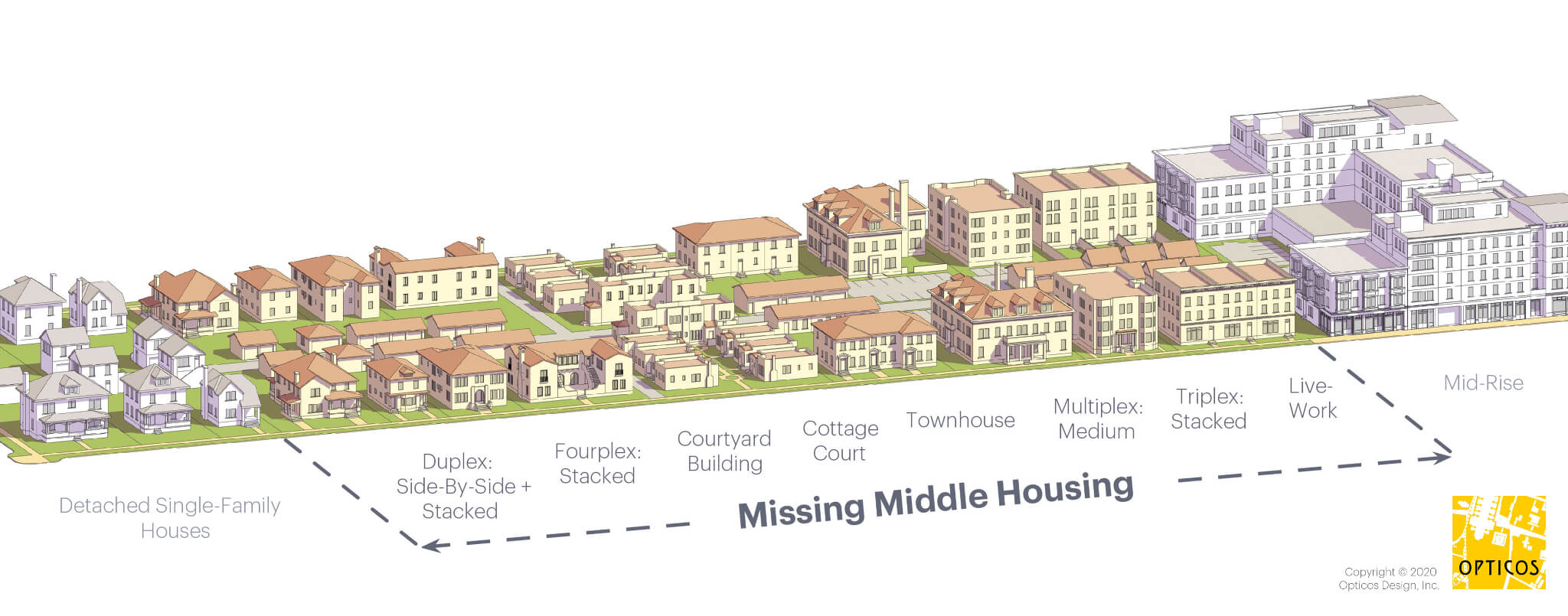

Cities may also seek to encourage development of missing middle housing. Designer Daniel Parolek coined the term "missing middle" to denote "a range of multi-unit or clustered housing types compatible in scale with single-family homes that help meet the growing demand for walkable urban living." These are "missing" because of unmet demand, estimated by Arthur C. Nelson in a 2014 conference paper at 35 million units. Missing middle housing includes duplexes, fourplexes, small multiplexes, bungalow courts, townhouses, courtyard apartments, carriage houses, and apartments-attached-to-workplaces. (See website for examples as well as advice to designers.)

|

| Source: missingmiddlehousing.com |

Single-use zoning leads to the lack of such development. Parolek notes: (1) codes usually skip from single-family detached homes to apartment complexes which tend to be large; (2) they don't allow for blended densities; and (3) lack of flexibility in parking and open space requirements discourages smaller units. A form-based code, on the other hand, can create a range of housing types compatible with the community's vision.

Then for each form-based zoning district a specific range of housing types is allowed. For example, in a T3 Walkable Neighborhood a single-family detached type, bungalow court, and side-by-side duplex may be allowed, or a urban T4 Urban Neighborhood zone would allow bungalow courts, side-by-side duplexes, stacked duplexes, fourplexes, and the multiplex: small type, even though the densities of each of these types can range dramatically. Each type has a minimum lot size and maximum number of units allowed, thus enabling a maximum density calculation as the output. (missingmiddlehousing.com)Cedar Rapids, which lost a lot of housing and commercial buildings to a massive flood in 2008, may have more opportunity than most cities to remake its landscape. Even here, change will come slowly. The main idea is to remove from the law persistent obstacles to traditional, human-scaled development, and where possible to use the zoning code to shape development in the community interest.

WORKS CITED

Andres Duany, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk and Jeff Speck, Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream (North Point, 2000)

Robert Fishman, Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia (Basic, 1987)

Arthur C. Nelson, "Missing Middle: Demand and Benefits," paper prepared for Utah Land Use Institute conference, 21 October 2014

WEBSITES

"Center for Applied Transect Studies," http://transect.org/

"Center for Applied Transect Studies," http://transect.org/

"Form Based Codes Institute," http://formbasedcodes.org/

"Missing Middle: Responding to the Demand for Walkable Urban Living," http://missingmiddlehousing.com/

JUST PUBLISHED! Ryan Holeywell, "How the 'Missing Middle' Can Make Neighborhoods More Walkable," Urban Edge, 29 March 2016

"Missing Middle: Responding to the Demand for Walkable Urban Living," http://missingmiddlehousing.com/

JUST PUBLISHED! Ryan Holeywell, "How the 'Missing Middle' Can Make Neighborhoods More Walkable," Urban Edge, 29 March 2016

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Book review: The Nature of Our Cities

Nadina Galle (left) and Lieve Mertens, with Dutch language editions of the book (Source: nadinagalle.com) Galle, Nadina. The Nature of Our...

-

Look at where we are! Can you believe it?? Crowds gather for the LGBTQ Forum in Cedar Rapids The first thing to be noted about the LG...

-

Heritage Foundation, Washington DC, on a cloudy day in 2012 The first thing you notice about Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation's ma...

-

900 3rd St SE: Loftus Lofts (186 units) under construction The New Bohemia neighborhood, located on the east side of the Cedar River south o...