|

| At Christmas I got COVID and this book! |

M. Nolan Gray, Arbitrary Lines: How Zoning Broke the American City and How to Fix It [Washington: Island Press, 2022], xii + 240 pp.

Way back in 2016 I got named to a steering committee for revisions to the zoning code in my city of Cedar Rapids, Iowa. I attended meetings for a bit over a year, then the meetings kept getting scheduled when I was teaching classes, then I went off to a sabbatical. The city now has a form-based code and no parking minima for certain core areas where there is going redevelopment after the 2008 cataclysmic flood. The rest of the city is pretty much the same. I doubt I was much help.

My thought at the time, inasmuch as I'm able to get back in touch with 2016-me, was that zoning reform could accomplish two objectives: (1) by allowing mixed uses, we could reintroduce some vitality to parts of the city and stop some of the destructive features of single-use ("Euclidean") zoning; and (2) by defining the form of construction instead of usage, we could streamline the development process and thereby lower construction costs. Based on our city's updated zoning map, linked here, we may not have gotten there

2016-me would surely have benefited from a hole in the space-time continuum that would have gotten me an advance copy of Arbitrary Lines, a brief but tightly-argued work by New York City-based planner M. Nolan Gray that promises to be the starting point for all future conversations about zoning. (Producing this book involved both Island Press and George Mason University's Mercatus Center, a collaboration I for one never expected to see.)

In less than 200 pages, Gray makes the case that zoning does more harm than good and should be abolished--no reform, just get rid of it. He notes that zoning was not practiced by local governments until the early 20th century, when a coalition of the privileged--commercial landlords, affluent homeowners, and nativists--deployed zoning to defend middle class areas from incursions by immigrants and the working-class (ch. 1). Subsequently it has operated to protect property values while limiting the supply of housing and making it thereby less accessible and more expensive (ch. 3), limiting movement to areas of the country with high-performing economies thereby restricting individual opportunity and overall growth (ch. 4), restraining racial minorities (ch. 5), and causing more resource consumption and environmental stress (ch. 6). Well, of course it has.

In chapter 8, Gray makes the case that fragmentation of metropolitan governments means that even the best-intentioned zoning code is going to be manipulable by powerful interests. In chapter 9, he commends the example of Houston, Texas, which has managed to grow quickly and remain relatively affordable while accommodating the well-off and not descending into land use chaos. "Even before zoning," he points out, "Industries need to be where land is cheap and transportation is accessible, and complaining neighbors are few and far between" (p. 152). But he also is pragmatic enough to recommend urgent steps short of outright abolition, including ending single-family zoning, abolishing parking minima, dealing with regulations on minimum floor area and lot size, and allowing single-room occupancy and manufactured housing in city limits.

This is really a lot to pack into a little book. I wish he had dealt with form-based codes, and spent more time on the difficulty of achieving housing affordability when so many people have their principal investments in their home i.e. their golden years depend on housing being less affordable (cf. Hertz 2016). On the latter point, he allows "it suggests a bleak future" and any "gains may be on weak political future" (p. 64). Maybe by spreading information about the social harms of zoning we can appeal to people's better angels? There certainly has been movement in the angelic direction, such as Minneapolis abolishing single-family zoning and Fayetteville liberalizing its ADU ordinance.

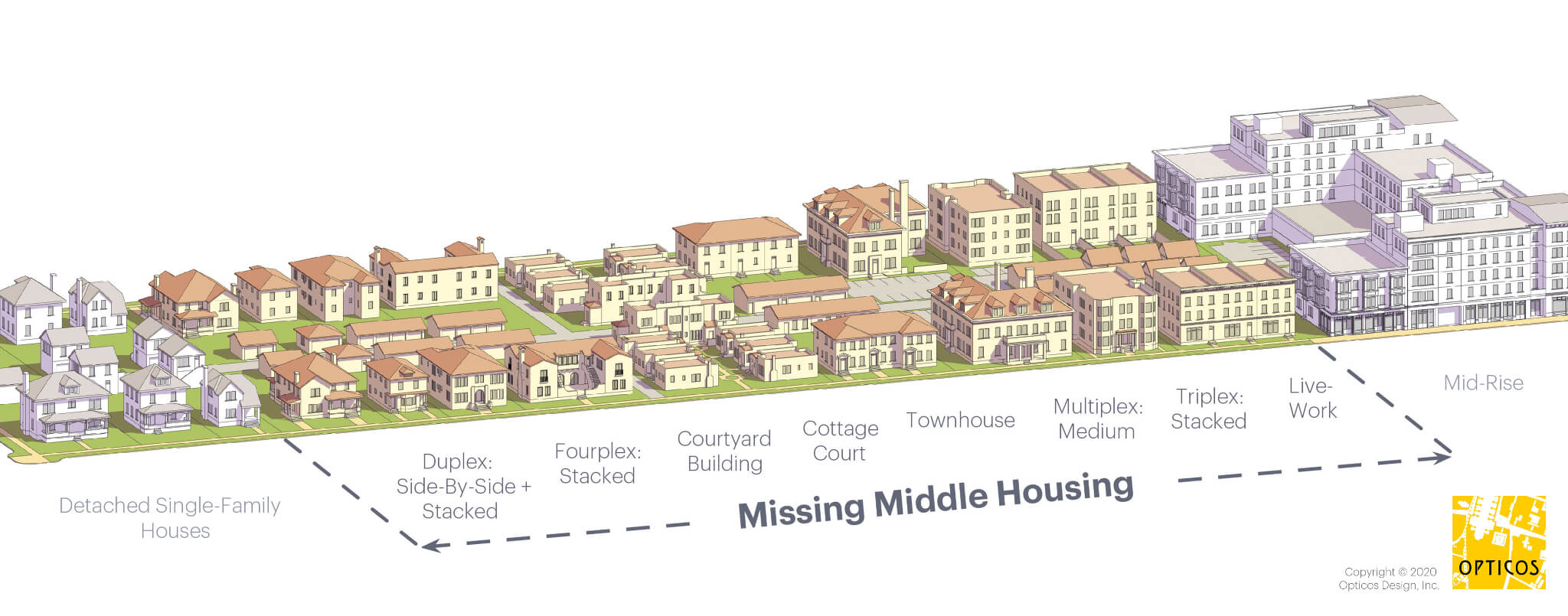

Cedar Rapids is a small city with a lot of farmland beckoning us to sprawl further. Maybe we will benefit--our governor says it's already happening--from people relocating from high-demand areas. Gray warns this "at best just buys us time... Absent fundamental reforms, the housing affordability crisis will only spread" (p. 65). So what could Cedar Rapids have achieved, had it decided in 2019 to go Full Houston with its land use policy? Less cost pressure on hot neighborhoods like New Bohemia and Kingston because those developments could be spread around the city? Manufactured homes that aren't on the absolute fringe of the city? Missing middle housing and accessory dwelling units in connected places? Enough density in spots to support better public transit? More intense development closer to surviving public schools?

Hey, a fellow can dream, can't he?

SEE ALSO: "Re-Zone CR Open House," 20 June 2018