Having spent fall semester teaching from Happy City by Charles Montgomery, I can not imagine a more appropriate Christmas present than Happy City, a new game for ages 10 and up from Gamewright. Thanks to my wife Jane--who has also used Happy City in a class--for this astutely-chosen gift!

Happy City has no relationship to Montgomery's book. He is not mentioned in the game materials or on the website, so I assume the coincidental titles are exactly that... coincidental. Even so it practically begs for comparison, which I am about to undertake. Keep in mind, though, this card game is aimed at children; if you're cruising the Internet looking for someone slagging a children's card game, you should definitely check out Yu-Gi-Oh: The Abridged Series on YouTube. You will not find that tone here.

On the other hand, the book Happy City, while accessibly-written, is a book for adults who have a tolerance for complexity and counterintuitive research findings. It would be hard for the most brilliant designer to translate Montgomery's argument into a game for the whole family intended to be played in under 30 minutes.

Playing Happy City

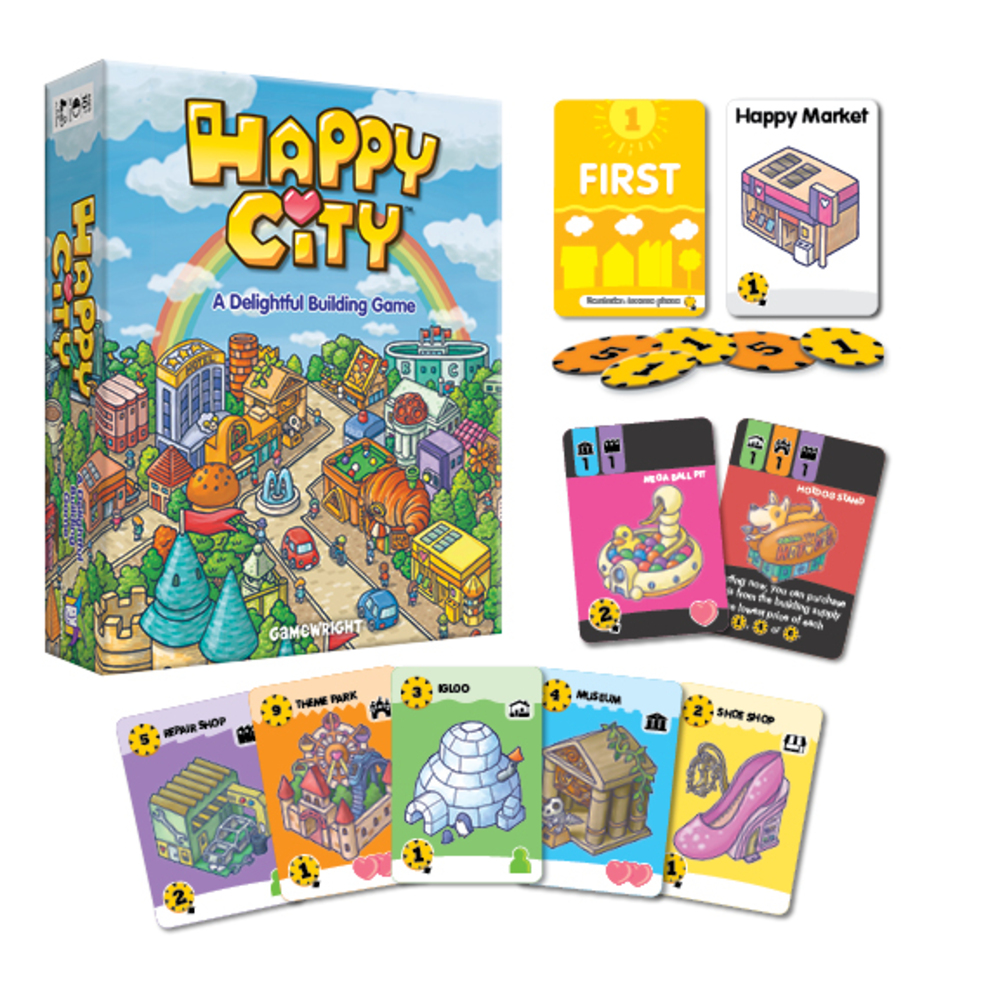

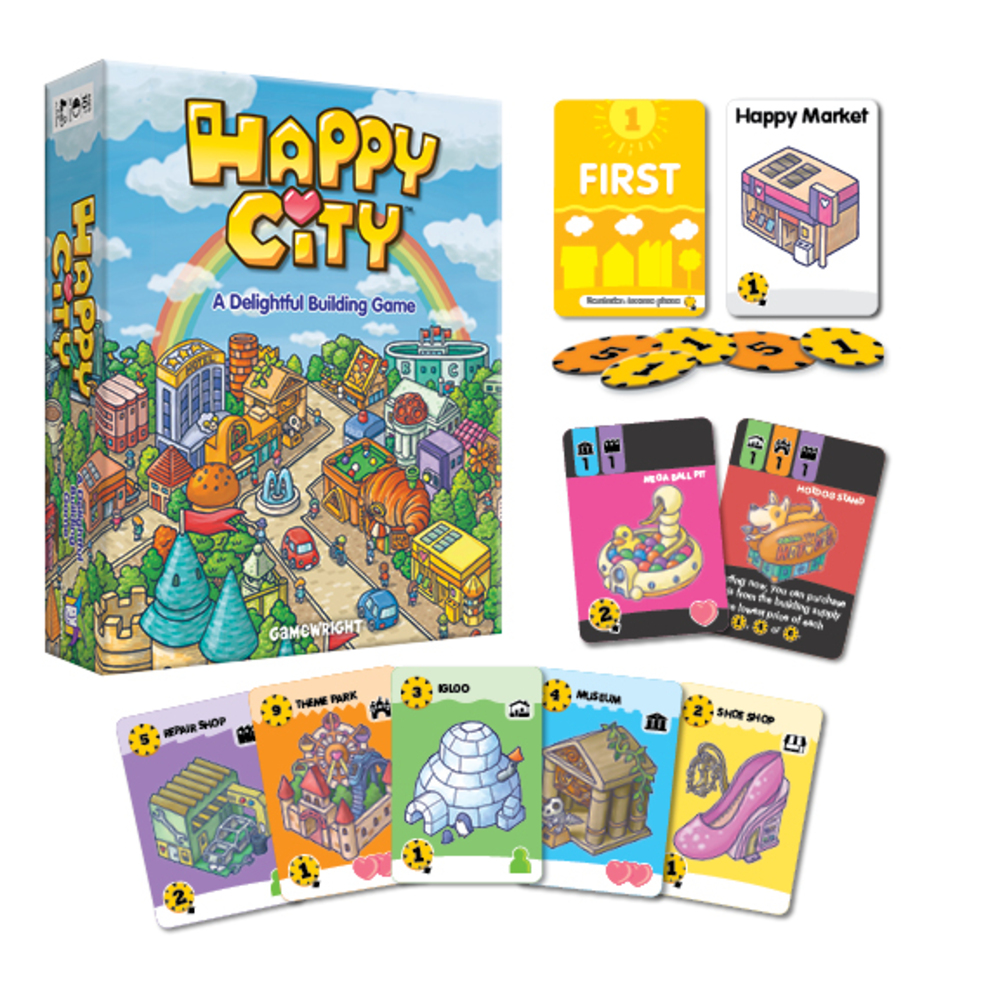

Happy City is a game for 2-5 players. Play goes in order of how recently each player has in their actual life traveled to another city. Each player starts with a mildly-profitable store, and from that attempts to build a city with high population and high citizen happiness. Each building is represented by a card; the game ends after one player's city has ten cards. The winner is the one with the highest overall score, determined by multiplying the population score and the happiness score.

|

Source: gamewright.com/product/happy-city

|

The key to building your happy city is to maintain a positive flow of income, so that you can buy the features that will bring in people and/or make them happy and/or add to the city's income. The buildings come in several categories. Players are encouraged to draw from a mix of categories, though they may not use more than one of the same kind of card. Some examples:

- Happy Market: 1 coin of income (paid at the beginning of each round of turns)

- house: cost 1 coin, 1 population point

- apartment complex: cost 3 coins, 2 population points

- high-rise: cost 6 coins, 3 population points

- library: cost 2 coins, 1 happiness point

- repair shop: cost 5 coins, 1 population point, 2 coins of income

- restaurant: cost 5 coins, 1 happiness point, 2 coins of income

- casino: cost 7 coins, 2 happiness points, 2 coins of income

- ski resort: cost 8 coins, 3 happiness points

- steelworks: cost 1 coin, -1 (yes, -1) happiness point, 1 coin of income

|

I'd give our library at least two happiness points!

|

In time, with the right mix of card/building types, players can pick from a selection of bonus building cards (e.g. Superhero Central, Happywood Studios, Unicorn Ranch), which amp up both population and happiness scores. An expert version of the game has more bonus buildings and more complicated scoring.

Evaluation

Happy City does a very good job of modeling a number of factors related to city development. The primary importance of income, making it a prerequisite to any actual building, is a good way to put fiscal realities at the forefront of our considerations. The folks at

Strong Towns will be gratified that all income in the game is locally-generated. We are not relying on federal or state grants to grow our cities.

Calculating the final score by multiplying happiness by population is a good way to model the interaction of those two factors. A small number of people experiencing a lot of happiness is an enclave or an exclusive club. A large number of people experiencing low happiness are existing in a place, not citizens of it. A large number of people experiencing a lot of happiness is a happy city.

|

| Casino, Las Vegas NV |

A third good point is, even though the city is developing in a centrally planned non-organic way, at least the planner/player is responding to values that have been established externally (presumably, in the economic market or political arena) rather than by themselves. Players are not Robert Owen or Le Corbusier or

Marshal Tito constructing our own utopias, but working with preferences expressed by others. Last time I played, I added a casino to my city,

not because I believe they're in any way productive, but because I needed the income and the happiness points. (For the record, I think the game vastly overrates casinos and

sports stadiums on both counts.)

The biggest difference between Happy City and

Happy City is how each understands happiness. The game's high happiness scores for leisure and entertainment facilities suggests the authors equate happiness with personal fun and pleasure. Montgomery's book goes into considerable detail in questioning that sort of premise, describing in chapter 2 a more long-term feeling of well-being, and later arguing that extrinsic motivators like fun things to buy or visit are overrated by people as sources of happiness. It's intrinsic motivators like health and social connection that endure and contribute to feelings of well-being. As Mitchell Reardon, a senior planner at Montgomery's firm, told the

Shared Space podcast in March 2021:

We are social creatures, yet for decades city planning has sought to divide us. We're just trying to knit this back together, and COVID has really underlined how critical that connection is.

|

Shared streets, like at Washington's Wharf,

are essential to experiencing that place |

Urbanists like Montgomery spend less time on the commercial and industrial features of a town than on whether or not they're connected. In

Walkable City [Farrar Straus and Giroux, 2011]

, three of Jeff Speck's four components of walkability deal with the experience of the walk--does it feel safe? comfortable? interesting?--and only one with the walk's destination. Jane Jacobs spends the first three chapters of her landmark

The Rise and Fall of Great American Cities [Modern Library, (1961) 2011] talking about sidewalks. In part two, she articulates the prerequisites for urban success--mixed primary uses, small blocks, some older buildings, and concentrated population--none of which have to do with what specifically goes on those blocks or in those buildings. Toronto-based

880 Cities, which aims to make cities "great" for 8-year-olds and 80-year-olds, focuses their efforts on "your community's streets and public spaces." And so on.

|

Street musician on pedestrian-only Knez Mihailova, Belgrade

|

Montgomery devotes the middle third of his book to assembling neuroscience research and lived experience on how happiness can be designed. Creating spaces for informal gathering, often out of infrastructure previously devoted to cars, attracts people and helps build social connection and trust (Montgomery 2013, ch. 7). He quotes

Jan Gehl:

What is most attractive, what attracts people to stop and linger and look, will invariably be other people. Activity in human life is the greatest attraction in cities (p. 150). In a society where so many people drive to work yet experience daily unhappiness doing so (pp. 179-181), anything to enhance the opportunities to cycle or walk will improve the city's happiness. So will anything to help those on public transit, "the most miserable commuters of all" (p. 193). Finally, opportunities for refuge and experience of nature will relieve stress and restore our souls (ch. 6).

|

| Boyson Trail, Marion IA |

These aren't simple push-button interventions, either. They require a lot of trial and revision, and attention to different people's lived experiences in different places. That makes sense; after all, cities are "problems of organized complexity" (Jacobs [1961] 2011, ch. 22). It follows that any attempt to model all the complexity at the level of a two-dimensional board game is going to fall short, so let us not cavil at Happy City, which after all is a fun and quick play, and which gets a lot of the city right.

Just let's don't confuse amenities with happiness.

SOURCE: Charles Montgomery, Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2013.

SEE ALSO: