|

Corridor Urbanism favors bars for meetings.

Why not a church? |

The term third place entered the national vocabulary more than thirty years ago with the first publication of Ray Oldenburg's The Great Good Place [Paragon House, 1989], and the concept seems as popular as ever. Clearly, Oldenburg struck a nerve with his description of neighborhood gathering places lost in America's rush to the suburban model of development after World War II. The quest to recover authentic third places has been part and parcel of the back-to-the-city era that has marked the first two decades of this century.

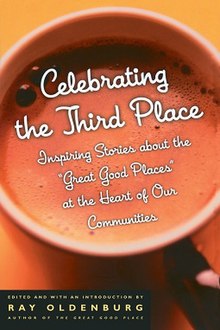

Meanwhile, the book went to a 2nd edition in 1999 (DaCapo), and then in 2001 he edited Celebrating the Third Place: Inspiring Stories about the 'Great Good Places' at the Heart of Our Communities (Marlowe), in which proprietors of third places tell their stories.

Oldenburg would rather describe third places than provide a crisp definition. The concept is complicated: The Great Good Place runs to 296 pages of text. On page 2 of Celebrating the Third Place, he does equate the term with "a setting beyond home and work in which people relax in good company and do so on a regular basis." His most common short formulation, though, is "informal public gathering places." "Conversation is the main activity," he argues (1999: 26):

Nothing more clearly indicates a third places than that the talk there is good; that it is lively, scintillating, colorful, and engaging.... The persistent mood of the third place is a playful one. Those who would keep conversation serious for more than a minute are almost certainly doomed to failure. (1999: 26, 37)

This conversation must cross friend groups to qualify fully:

The B.Y.O.F. (Bring Your Own Friends) tavern may initially offer a convincing illusion of a third place, particularly when it is crowded.... The illusion is one of unity, of everybody enjoying themselves together. Upon closer examination, however, one finds that there is no unity.... The individual entering alone is almost certainly doomed to remain that way. The patrons, by their choice of seating, the positioning of their bodies, the contained volume of their voices, and their eye movements indicate that invasion of their group by others is neither expected nor welcome. Nobody meanders from one group to the next. No one calls out to friends across the room. (1999: 171)

Sometimes The Great Good Place seems at war with itself, because the heyday of third places in America occurred in extremely gendered times. If you can have a men-only third place, can you slice and dice the public in other exclusive ways? Can you be a little bit inclusive? Now I'm even more uncomfortable than I was when I started writing this essentializing paragraph, but length constraints require we push on and essentialize, so essentialize we will!

The subtitle of Oldenburg's first book is Cafes, Coffee Shops, Community Centers, Beauty Parlors, General Stores, Bars, Hangouts, & How They Get You Through Your Day. Celebrating the Third Place includes

plenty of those, plus a garden store, a

gym, and a photo shop. Just being a cafe doesn't make you a third place, though; he warns against those who would co-opt the popularity of the concept for their own economic gain without providing authentic community:

Developers build houses and call them "homes." They build socially sterile subdivisions and call them "communities." It's called "warming the product." It's also happening with alleged third places. Officials of a popular coffeehouse chain often claim that their establishments are third places, but they aren't. They may evolve into them but at present, they are high volume, fast turnover operations that present an institutional ambience at an intimate level. Seating is uncomfortable by design and customers in line are treated rudely when uncertain of their orders. (2001: 3)

The third places are, then, predominantly small commercial establishments: "The best places are locally owned, independent, small-scale, steady-state businesses" (2001: 4). However, people gather in all kinds of places that don't fit that description, for all kinds of reasons. Can a sports stadium be a third place? How about a grocery store? A high school? A theater group? A Starbucks? A casino? Possum Lodge? A friend's basement rec room? An online college writing center?

What about a church? Mine had an orientation/planning meeting last weekend, and the desire to make our church a third place figured prominently in the discussion.

In chapter 2 of The Great Good Place, Oldenburg describes third places as a "leveler" accessible to the entire neighborhood and so expanding everyone's range of association; a "neutral ground" where no one whoever they are has pride of status (with the exception of well-established "regulars"); and a place where conversation is the main activity and main purpose for gathering. They are accessible at most times of day, informal so they accommodate people's home and work obligations, playful, and with a low external profile. At their core...

The first and most important function of third places is that of uniting the neighborhood... Places such as these, which serve virtually everybody, soon create an environment in which everybody knows just about everybody. In most cases, it cannot be said that everyone, or even a majority, will like everybody else. It is, however, important to know everyone, to know how they variously add to and subtract from the general welfare; to know what they can contribute in the face of various problems or crises, and to learn to feel at ease with everyone in the neighborhood irrespective of how one feels about them. A third place is a "mixer." (1999: xvii-xviii)

...in other words, similar to Jane Jacobs's theory of sidewalks, but one level up!

A church, however open it would like its doors to be, is constrained as an informal, public "mixer" by having a creed--though these vary widely in rigidity--and formal membership. Churches have a variety of associations for people, not all of them positive. Their main function is to hold worship services and to provide spiritual benefits to its members. Without products to sell, they rely heavily on fundraising to support paid staff, outreach ("evangelism") to increase membership, and a bewildering array of committees that require members to staff. All run counter to the playful informality of third places, which might be why those tend to be small businesses, which have an owner and employees to keep the beer or coffee flowing and the restrooms clean.

Nevertheless, I've been in a few churches over the years that have some qualities of a third place:

Wesley United Methodist Church and Foundation, Urbana IL, runs a coffeehouse that hosted a broad clientele in the 1980s when I volunteered and quaffed non-alcoholic beverages there. (The church also had a large lounge that attracted students during the week for studying or naps; at least it did during the less security-conscious '80s.) Back then, at the risk of shocking the young people of today, there weren't coffee houses dotting the landscape, and if you wanted to go someplace near campus that wasn't a bar you had to go to the Etc. The main menu items were "wassail," a very sweet and highly-caffeinated beverage made from Dr. Pepper syrup, and "orts," a sort-of-cheese curds made from Velveeta brand sort-of-cheese. The Etc. is in one corner of a large building, and I'm not sure how many of its customers even know it is attached to a church. In my time it was only open eight hours a week (8-12 Fri/Sat), so limited on the accessibility dimension.

|

| Getting ready for Jazz Night, March 2018 |

Westminster Presbyterian Church, Washington DC, has Jazz Night every Friday and Blues Night every Monday--again, only a few hours a week, unlike a regularly-open coffeehouse or bar. Music venues are more for performance than for conversation, but at Jazz Night there are long breaks between sets when people wander all over the sanctuary/performance space to greet each other. Even more conversation can be had in the basement, where they serve delicious home-cooked food. I went there one Friday night to check it out, and after that I returned every time I could. I never attended a service at the church, though. I don't know how many people in the audience do, either, but I suspect it is a lowish percentage. What does the church get out of it? Some spillover increase in membership? Or just the joy of being a community institution?

Veritas Church, Cedar Rapids IA, is located toward the south end of downtown Cedar Rapids, easily walkable from any of the core neighborhoods. They have been selling Dash Coffee Roasters products in their lobby for a couple years, and are currently open 7:30-3 weekdays. (They close at 12:30 Fridays.) They have plenty of space, so it's easy to socially distance, and the open floor plan facilitates seeing other people who happen to be there. I attended one service at Veritas in maybe 2017 to see a former student get baptized, and probably won't be back, but that doesn't matter to being welcomed and feeling comfortable at the "cafe."

Each of these churches is built to the street in a walkable neighborhood--design matters!--and they have been able to provide something the neighborhood needs (a safe meeting place during a pandemic, live music, non-alcoholic "wassail") that is sufficiently impelling to overcome any reservations on the parts of attendees about whether they belong there. It's important also that each church sustains awillingness to devote ongoing space, energy, and custodial time to activities which ask nothing of attendees regarding creed or membership, and do not contribute (much) to church attendance, maintenance, or finances.

Looser affiliations may be where the practice of church is heading in the 21st century, but not all are buying it. Notably, four people at our church's vision discussion--all men, curiously--advocated for more efforts towards increasing membership and financial contributions. There are valid reasons to pursue those goals, too, but they seem at cross-purposes with becoming a third place.

SEE ALSO:

Johnny Dzubak, "What is a Third Place and Why Do You Need One," The Art of Charm, 8 April 2015, and "Third Place, Part Two: Finding the Right Third Place for You," 15 April 2015. Dzubak has a different way of essentializing Oldenburg than I do, with more stress on individual benefits and less on community functions of third places. Nevertheless, it's an interesting take. And I wish Dzubak had been my older brother forty years ago when I really needed these life lessons!

Sara Joy Proppe, "Sit On It," Strong Towns, 21 January 2016. Houses of worship can contribute a lot to neighborhood walkability by providing places to sit in their yards.

.jpg)