|

| More like this? Rooming houses in the MedQuarter district |

The Cedar Rapids Gazette headline Sunday ("41K in Iowa Fear Eviction as Moratorium Nears Its End") is overblown, but the reality is scary enough. According to the U.S. Census Bureau Housing Pulse Survey, about 11000 Iowans say they're very likely to be evicted from rental housing in the next two months, 21000 say they're somewhat likely to be evicted, and 9000 say they're somewhat likely to be foreclosed on property they own. Even 11000 is a lot of homeless people, relative to available housing stock in our state. Similar results are posted for other states. How about 1.2 million for a national figure? All told about 7 million renters owe accumulated back rent that has been estimated in a range of $11-53 million, according to Mary Cunningham of the Urban Institute (Urban Institute 2021, slides 16 & 19).

Despite a surge in construction both of single-family and multi-family dwellings in the last couple of years, the United States remains about 3.8 million units short of where it needs to be, and existing housing has accumulated $45 billion worth of needed repairs, according to the annual report just published by the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies (Sisson 2021). Rapidly rising home prices (Nicholson, Merrill, and Sam 2021) have helped existing owners while creating obstacles for first-time homebuyers and renters; other issues include racial and generational inequities and lack of housing near jobs.

The Census Bureau and Harvard Center reports testify to the persistence of housing issues in America, as well as to their complexity. Those challenges can be sorted into three or four buckets: affordability (supply of housing at the right price points); connections to jobs and the larger city, and the avoidance of concentrations of poverty; and stability amidst threats of job loss or displacement through gentrification. The physical condition of existing housing might be a fourth set of issues.

1. Affordability/Supply

Nationally, the home price-to-median income ratio is rising; currently it's 4.4, though that contains a wide range of differences. San Jose, California, leads the country with a ratio of 10.9, and cities like that face a different set of problems than cities like Cedar Rapids, where it's about 3 metro-wide, or Iowa City where it's about 4 (Hermann 2018). Everywhere the market for for-sale homes is "red hot," said Daniel T. McCue of Harvard at the report's June 16 rollout, with demand overwhelming supply as millennials enter the market, resulting in higher real prices than any time this century.

Rental prices are also up nationwide as well, with well over half of those making less than $50,000 a year paying more than a third of their income on rent, meaning they're one setback away from eviction. Rental vacancies have increased in high-rent urban areas, though that seems to have peaked. Sociologist Matthew Desmond, author of Evicted [Crown, 2016] showed a chart at a Bipartisan Policy Council webinar showing that median rents have doubled in the last twenty years while incomes are steady:

|

| I can't get this chart out of my head... |

In locations like Cedar Rapids, discussions of housing affordability focus on people at the low end of the pay scale, those with disabilities, and those with criminal records. A 2017 forum noted federal funding Section 8 vouchers don't come close to covering all those eligible, local resources for those experiencing homelessness are limited, and non-profits like Habitat for Humanity have limited production capacity. Those landlords who do accept Section 8 vouchers are subject to extra mandates and inspections, and might could use funding to help them with repairs and updates. Beyond this, there might still be different kinds of issues higher on the income scale; unlike in San Jose, teachers and firefighters in Cedar Rapids can afford homes, but do they face different financial issues once they've bought them?

Urbanists have long advocated making accessory dwelling units (sometimes called "coach houses" or "granny flats") legal; Chicago enacted a three-year trial run this year with impressive response so far. Narrower streets would allow more land to be put to productive use (Merrefield 2021)--among many other benefits. Cambridge, Massachusetts passed an Affordable Housing Overlay ordinance in 2020 that loosened zoning restrictions on construction citywide (Gibbs 2021).

Shane Phillips argues increasing supply while maintaining affordability and stability requires some form of government intervention in the housing market:

A well-regulated private housing market can serve a large portion of our population, and tenant protections paired with rental housing preservation can assist even more. But there will always be people who are left behind by these efforts—sometimes temporarily, sometimes permanently. Acting through the collective will of our local, state, and federal governments, we have a responsibility to provide support to those who need it and to live up to our professed belief that housing is a human right. This may take the form of rental assistance, publicly subsidized housing construction and acquisition, and a host of other programs (2020: 33).

Awareness of policy consequences is important: Cities can avoid San Francisco's infamous tenant protections that are blamed for constraining supply, but prices--and displacement--have also risen in less restrictive cities like in Texas and Washington even though housing supply has increased (Phillips 2020: 24-28).

Anthony Simpkins of Neighborhood Housing Services of Chicago told an Urban Institute panel that rental housing won't close the racial wealth gap, but homeownership policies will.

Affordable rental housing does not generate generational wealth. It's never going to close the racial wealth gap.... Today, in a high-cost city like the City of Chicago, a homeowner can pay less for their mortgage than they pay for rent. But when you look at the rules and regulations [related to affordable housing policy], they all skew towards supporting rental housing. There's very little room and very little ability to use these resources to build and expand homeownership among people of color.... It's all about access to capital (Urban Institute 2021, at about 59:48)]

2. Connection

A great deal of the new construction is in the suburbs and in non-metro areas, where it's easier to develop by the batch, and where zoning favors single family homes. You can also get more home for the money, although the savings can get eaten up by transportation costs; in metropolitan Chicago, for example, the closer a median-income household is to the city center, the less their total housing-plus-transportation costs. (See also the interactive maps at the Center for Neighborhood Technology website, including total driving costs by location, housing + transportation affordability index, and access to jobs by transit.)

|

| Apartments in the former Monroe School rent for $695 a month, but the Walk Score is 34 |

Residential concentrations of poverty are problematic for children, who do less well in life than those raised in more socioeconomically mixed areas (Chetty, Hendren and Katz 2016). They are problematic for adults, who have less access to economic opportunity as well as lower life expectancy (Ludwig 2014). Distance from affordable housing to jobs creates the transportation nightmares particularly for the poor and near-poor that Steven Higashide (2019: 92) calls "mobility redlining."

Simpkins talked about "building communities that have been left behind" as an essential part of remedying the racial wealth gap (Urban Institute 2021, at about 1:01:50). Most areas of concentrated poverty have not gentrified since the 1970s, but in fact have gotten worse off (Cortright et al. 2014). Can cities provide incentives to locate jobs that pay well near low-income areas, and discourage large corporate campuses in remote locations? Or to encourage developers to build affordable housing near areas of economic growth?

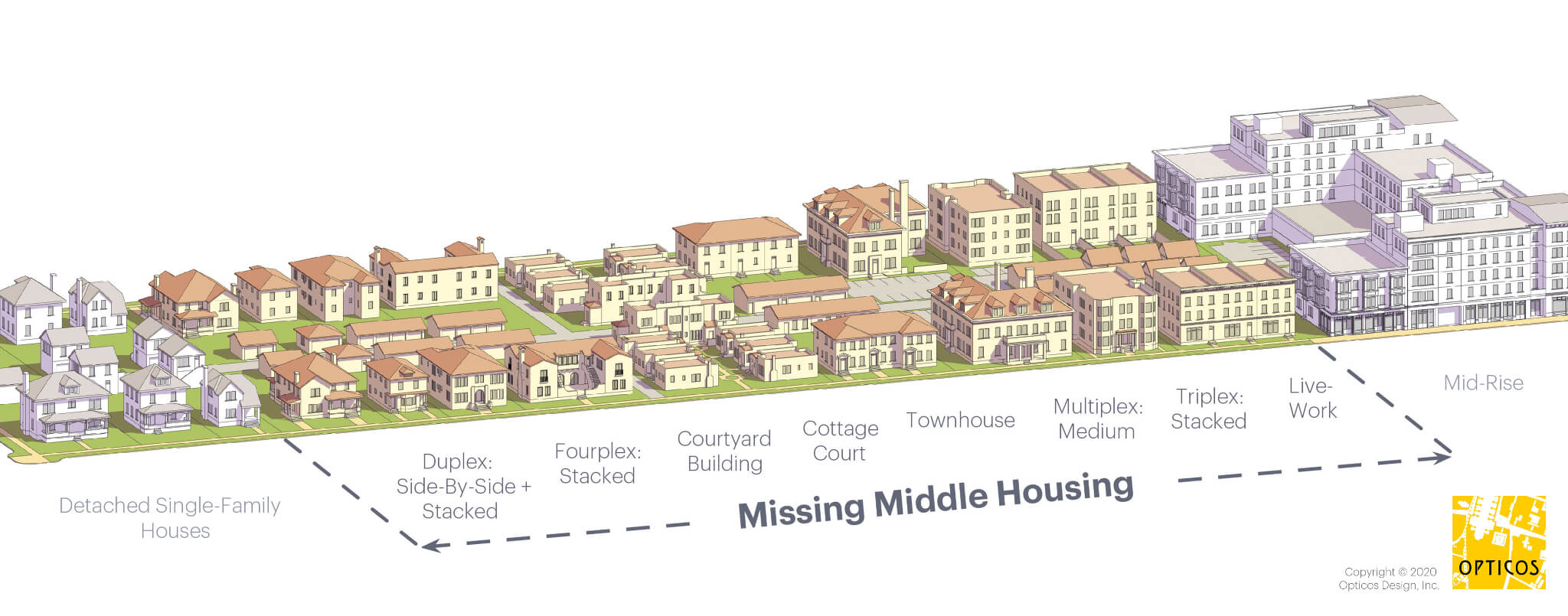

Options for cities include zoning reform that allows a greater variety of housing in a given area (Cortright 2017); Inglewood, California is planning zoning changes to allow more housing and commercial space near Metro rail stops (Sharp 2021). (See this post from 2017 for more on these issues.)

|

| This four-plex is four blocks from my house. |

| |

| So is this two-plex. If they were even closer, would I be less wealthy? |

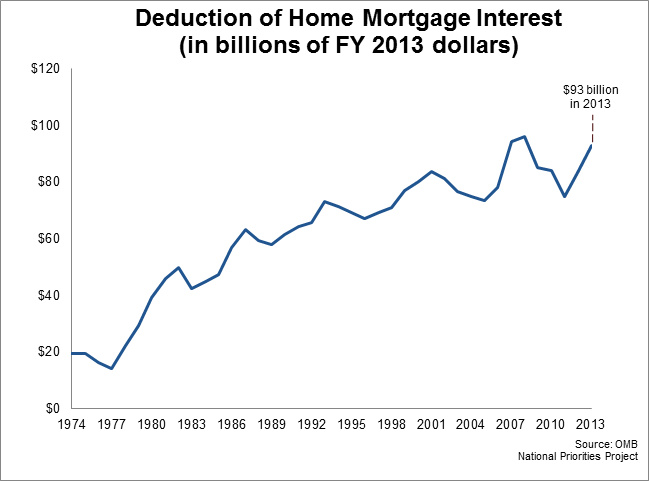

Cities can reform zoning codes to allow the production of small fourplex apartment buildings ("missing middle" housing) in residential neighborhoods (Holeywell 2016, McGlinchy 2017). Access to capital can provide "ladders" for those with very low income, as well as attracting middle class people to disinvested neighborhoods (Simpkins, in Urban Institute 2021). The national government can revisit the mortgage interest income tax deduction (Quednau 2017), as its value for most filers was eliminated by the 2017 tax act.

Local transit connections can be improved almost everywhere, and certainly could be in my city. Dharna Noor (2021) points out "investing in public transit isn't just a good idea for the climate and commute times. It's also a good way to ensure everyone has access to opportunity, including the opportunity to relax. Imagine if access to parks and lakes weren't limited to those who can afford to buy, maintain, and park their cars. That could go far in improving access for exploited, poor communities who are disproportionately harmed by highway pollution."

But is a ridership model compatible with where Cedar Rapids is currently building affordable housing (Pioneer Avenue, Johnson Avenue, Blairs Ferry Road, e.g.)? I would think not.

3. Stability and Gentrification

As land values rise, and incomes do not, evictions have soared: Desmond cited a figure of seven evictions per minute nationally in 2016 (Bipartisan Policy Council 2021). Annually there are more than a million more evictions than there had been foreclosures at the height of the housing crisis, with many associated bad effects on individual lives. Black [and Latinx] renters have about twice as high a rate of evictions as white renters. Evicted renters bounce from place to place because (quoting Desmond) they "are already living at the bottom of the market, in places they can't afford."

Stagnant incomes are one cause of housing instability; another is gentrification. Gentrification occurs where some circumstance has changed raising the potential value of housing far above its actual price (known as a "rent gap"). Recently middle-class demand for urban living has risen as amenities have improved, crime has decreased, and frankly fashions have changed. Gentrification can be good for places, and the people that live in them; at best it improves economic opportunity, public services and facilities, and the tax base. At worst it raises costs for those who stay, and drives others to less connected and less-well-off places (Florida 2015b; see this post from 2016 for a more detailed review of the debate). (For an argument that a focus on gentrification misidentifies the cause of problems with affordability and stability, see McMillan 2021.)

As rents go up, or property taxes rise on homes, some residents are forced to move to more affordable areas. Shane Phillips recounts one California experience: "A $5 billion stadium was proposed in Inglewood and rents and home values skyrocketed nearly overnight; even if the city had allowed for infinite development to meet the growing demand, thousands of households would be displaced before relief ever arrived. These changes were entirely outside the control of local residents, and yet they were the ones to suffer the consequences" (2020: 13).

Alexander Garvin's book about downtown areas discusses the displacement of people along the way to prosperity: "Increasing demand led to increasing rents and the inevitable gentrification. The rental tenants, who had pioneered loft living and could not afford to remain in the area, were replaced by occupants who demanded and received better fixtures and services for their higher rents. But condominium occupants either remained in a much-improved neighborhood or profited from selling their residences at the appreciated value" (2019: 37). Increasing housing supply might mitigate gentrification "if the citywide housing supply is increasing faster than population growth" (2019: 159), but resurgent value of districts like Cincinnati's Over the Rhine seems to depend to a frustrating extent on getting rid of the "undesirable people" (2019: 134). Either way, as places gentrify, their former residents are going somewhere, and where they go should not be a matter of indifference to policy makers.

Rising values create incentives for property owners like MidCity Financial Corporation in Maryland to convert low-income housing developments into mixed-income mixed-use (Milloy 2021). At the Harvard report rollout, Gary Anthony of the National League of Cities argued that construction of one- and two-bedroom apartments is not an answer for families who have been priced out of their single-family homes, and advocated for "race-specific anti-displacement policy."

Cities could improve access to transportation and other amenities more broadly, to reduce the value premium on accessible places (Florida 2015a). Washington, D.C. is redeveloping a closed hospital in the Congress Heights neighborhood with affordable housing as well as an entertainment facility anticipated to create jobs (Steuteville 2021). Other options include inclusionary zoning requiring developers to include below-market-rate housing (S. Williams et al. 2016, Kaplan 2014); improving housing choices by loosening zoning restrictions in order to provide more options like living above your shop (Marohn 2015); limiting increases on property taxes (T. Williams 2014); and mitigating culture clashes by facilitating communication between the recently-arrived and long-term residents (Saunders 2016).

Conclusion

Shane Phillips argues for balancing the many interests involved in housing policy:

We must design pro-housing policies that target development where it will benefit the most people (such as where housing costs are highest or job concentration is greatest) and that discourage it where it may do the most harm (such as on sites where dense concentrations of renters already live, especially in lower-income communities and communities of color).

We must design pro-tenant policies that protect renters living in affordable homes while ensuring that development remains a profitable venture on sites where tenants aren’t threatened and it can do the most good.

We must increase spending on rental assistance and affordable housing construction, and complementary zoning reforms and renter protections must be in place to make sure those funds are spent effectively (2020:42-43).

But he makes an exception to all that balancing by prioritizing affordability, even though, for many current owners, increased supply threatens the value of their property. It is an inescapable fact that home equity represents the major if not the only source of retirement savings. "Owning a home is integral to financial security for most families in the United States, and rising home values continue to give the government cover for skimping on retirement programs such as Social Security and pensions," but "ever-growing property values are completely incompatible with long-term housing affordability" (2020: 61). So, at the fundamental level, focus on broad affordability and the many social and quality-of-life benefits that would bring, and figure out some other way for people to accrue wealth.

|

| In the 19th century, Jacob Riis depicted squalid housing conditions in New York City. An exhibit of his photographs is now at the National Czech and Slovak Museum and Library in Cedar Rapids. |

SEE ALSO

Bipartisan Policy Council, "Eviction Prevention Now and After COVID-19" [webinar], 23 June 2021 #harvardhousingreport

Alexander Garvin, The Heart of the City: Creating Vibrant Downtowns for a New Century (Island, 2019)

Annie Gowen, "She Wanted to Stay. Her Landlord Wanted Her Out," Washington Post, 28 June 2021

Steven Higashide, Better Buses, Better Cities: How to Plan, Run, and Win the Fight for Effective Transit (Island, 2019)

Norman Van Eeden Petersman, "Could You Move in Next Door?" Strong Towns, 23 June 2021

Shane Phillips, The Affordable City: Strategies for Putting Housing Within Reach (And Keeping It There) (Island, 2020)

Prevention Institute, "Healthy Development Without Displacement: Realizing the Vision of Healthy Communities for All," July 2017

Urban Institute, "Stable Housing is a Critical First Step Toward Racial Equity" [webinar], 29 June 2021 #liveaturban